What would you learn about the current war in Afghanistan if you were to take as your sources several current magazines, say People, The New Yorker, and Newsweek? The story that would come into focus from such disparate sources may not offer a complete timeline of events, but it would provide a sense of what the people reading those publications cared about: a soldier’s homecoming, an intimate analysis of a general’s decisions, a photo montage of a raid.

Kathleen Diffley, a 2012 Obermann Fellow-in-Residence, has been taking such an approach to reading the history of the Civil War for more than three decades. During graduate school, Diffley (English, CLAS) was told that the Civil War was considered unwritten by literary scholars. She was dumbstruck: “How could the watershed event for American historians simply not have happened in the literary world?”

Seeking alternative sources, Diffley started researching periodicals from the era, beginning with Harper’s Monthly. Periodical studies, now an interdisciplinary field with scholars haling from fields like history, journalism, and women’s studies, was almost non-existent at that time. “There wasn’t even a clutch of fellow travelers,” notes Diffley, much less databases to ease the way.

For her first book, Where My Heart Is Turning Ever: Civil War Stories and Constitution Reform, 1861-1876, Diffley examined the ways in which a series of rhetorical strategies that repeated themselves in periodicals, such as recollecting the past in the form of old homestead stories, intersected with Congressional debates regarding Reconstruction amendments to the Constitution. Now in a related book, The Fateful Lightning, she is examining the telling of the Civil War and its aftermath via a contemporary magazine culture that was shaped by market concerns.

“In this book,” says Diffley, “I’m more focused on the creation and dissemination of the magazines themselves, the contemporary technologies and shifting social dynamics that affected how periodicals were created.”

Several phenomena energized and empowered the magazine industry at that time, she notes, including the growth of railroad lines, so that the geographic locale of potential readers expanded hugely. Also, readership exploded because of wartime life in camp. Men who had read only the Bible or farming journals suddenly read for pleasure to fill the long, boring periods during winter months and between battles. When they returned home, they continued reading and magazine subscriptions soared.

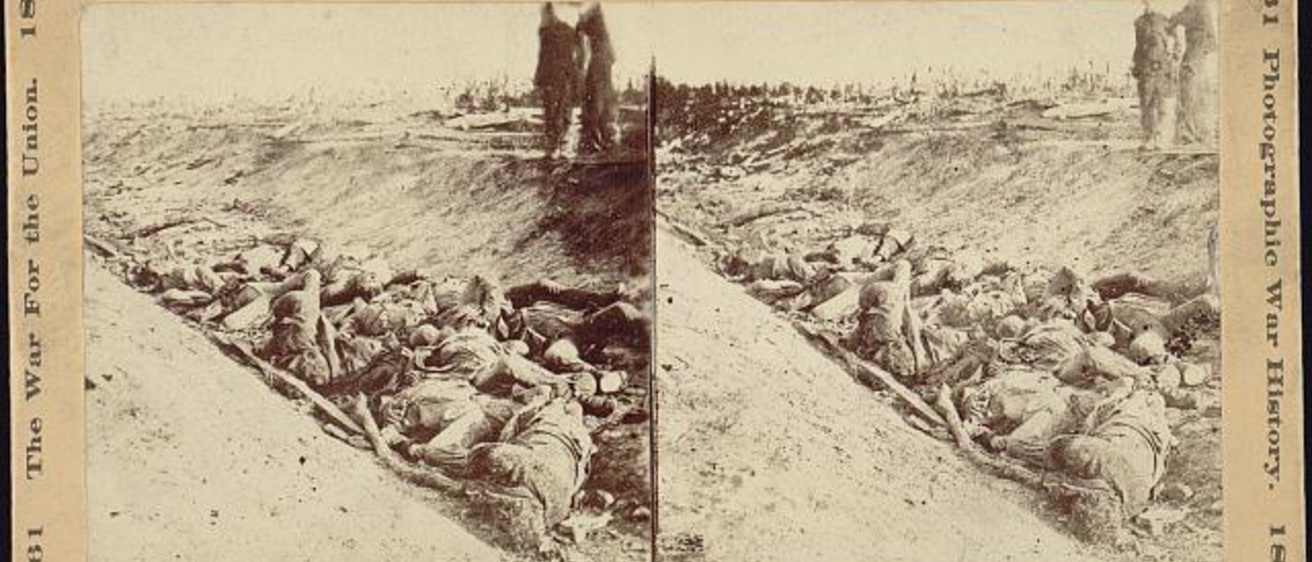

Another important evolution in magazines was the rise of photography, which was soon changing what periodicals engraved and would shortly substitute for wood engraving altogether. At the time, photographs were often seen as “sun-pictures,” what Diffley describes as “transparent, less constructed than artistic drawings, filled with the irrelevant details of ordinary life.” An engraving made from battlefield photographs of Antietam, for example, added clouds, filled in gaps, and offered a picturesque scene. By comparison, the well-known photos that Matthew Brady exhibited were spare, littered, and frequently shocking.

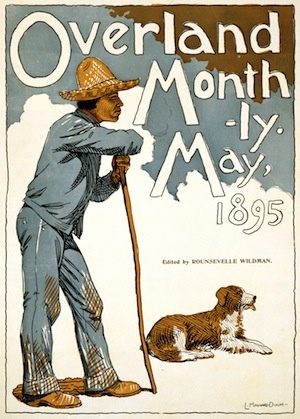

In addition to these evolutions in periodicals, Diffley is also looking at how periodicals differed regionally. The Overland Monthly, for example, was published in San Francisco, a city that was simply too far away to have a sizable population of free blacks and freed slaves shunned in ghettos. By contrast, Baltimore’s Southern Magazine arose in a city that had two of the country’s largest populations of African Americans and German immigrants. How these shifting demographics guided whose stories were told and whether “Africans” became “Americans” is also central to Diffley’s book.

Diffley laughs when she compares her earlier research in periodicals to her current work, given how much easier digitization has made the task. “Full runs of periodicals are available a clickety-click away,” she says. “You can search every time ‘postal service’ comes up, something that would have taken incredible time and patience in the past.” Some days, she regrets losing the serendipity of earlier searches. “You miss the rag content of the paper and the water stains, even the scent of the past and how it hung on the page. But I’d probably still take easier!”