“Poets to Come” in Five Languages

Ed Folsom has spent his career deciphering the works of Walt Whitman. After decades of reading and re-reading the quintessential American author, Folsom has had some unexpected new insights into his work by reading translations from German, Spanish, Italian, French, Portuguese, and Polish.

In June 2011, Folsom, who is the Carver Professor in the Department of English (CLAS), led the Obermann Summer Seminar, “Walt Whitman International: Literary Translation and the Digital Archive.” The goal of the weeklong seminar, which included a dozen scholars from six different countries, was to investigate how translation could become a useful tool in understanding Whitman’s poetry.

The idea for the seminar sprang from an earlier Obermann seminar that was supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1992 on the occasion of the centennial of Walt Whitman’s death. One session of the 1992 meeting had been on translation. It opened unexpected and, according to Folsom, “spectacular” conversations.

Whitman's Global Appeal

At that same time, Folsom (pictured above) and Ken Price (English, University of Nebraska-Lincoln) were initiating The Walt Whitman Archive, an early digital humanities project that has evolved into one of the preeminent resources for scholarly work regarding Whitman. The Whitman Archive remains one of the most impressive, widely admired, and ever evolving digital open source projects in the digital humanities.

Feeling a responsibility to the Archives’ growing international audience, Folsom and Price added a translations section to the site while also wondering what insights the process of translation could offer about the poems. It was this question that was at the heart of the summer seminar. As Folsom writes, they wanted to know what “multiple attempts to translate the same poem might tell us not only about the interpretive act that all translation inevitably is, but also about the original poem itself.”

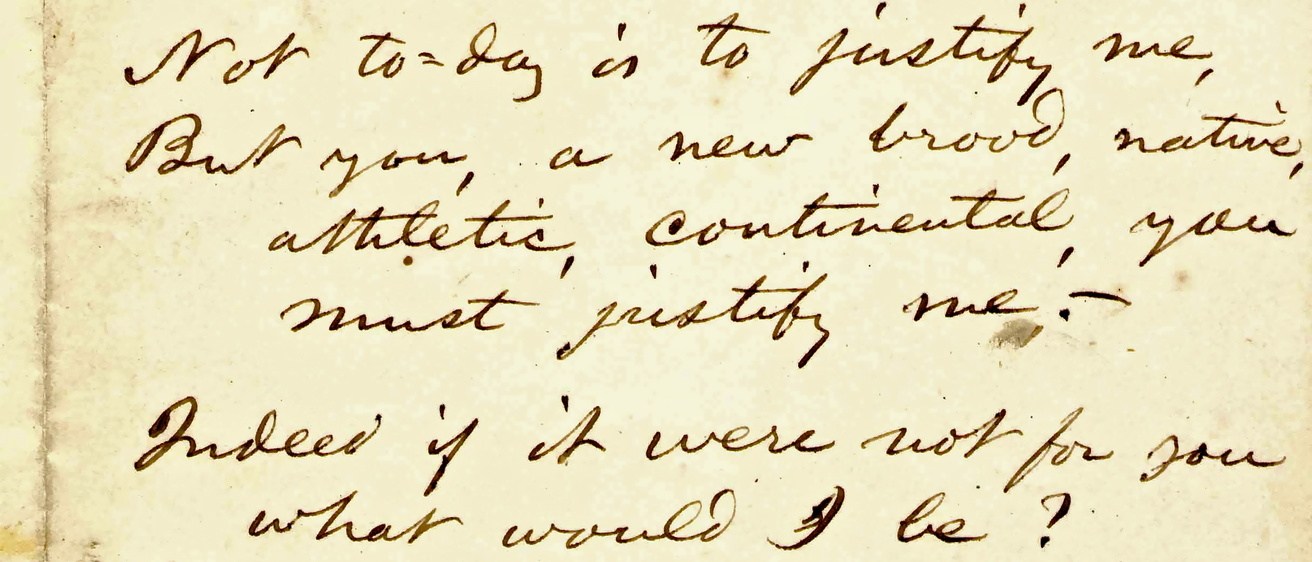

Each seminar member brought all of the published translations they could identify of six different Whitman poems to the table. The group located up to 80 translations in Spanish but fewer than 10 in Polish. Intending to get to all six poems, Folsom opened the seminar with “Poets to Come,” a short, well-known Whitman poem. They never left it.

Back Translating as a Tool for Discovery

It was a revelation that this single poem and its translations provided ample fodder for an entire week of conversation and the resulting scholarly essays. Much of the discovery came from the process of “back translating.” This is a common exercise used to teach translation and involves taking an already translated piece of writing in the translator’s native tongue and translating it back into English. The next step is to compare the original English piece with the back-translated version: the difference between the original poem and the back-translated version will pinpoint interpretive decisions made by the original translator. The decisions that the translator has made about such issues as alliteration, metaphor, syntax, and connotation form the basis for critical analysis and interpretation—leading to a deeper understanding of the work being translated.

As translator and seminar participant Russell Valentino describes the process, looking at the original provides an opportunity “not to show that the translators’ versions are all wrong, but to show how the whole process is filled with variation and minute choices that often make big differences in terms of expression and reception, and also, most importantly, to show how the non-English poem they've translated is a work unto itself, with a host of locally inflected nuances that are as untranslatable as the English version from which it came.”

Locating Points of Ambiguity

Of course, the Summer Seminar could contain no such “reveal”; everyone knew the original poem intimately. The group was initially resistant to the laborious process, but quickly realized its value.

“We would find a lot of agreement among the multiple translations for several phrases and then we would come upon a phrase or a word or an image where there was a lot of disagreement,” notes Folsom, “which would suggest ambiguity. We could then return to the original poem in English and see the ambiguity and complexity that many of us had never noticed.”

As one example, Whitman’s use of “you” as an ongoing character in his poems challenges translators to decide between the familiar and formal (as well as singular and plural) forms of “you” that other languages require but that the English “you” leaves ambiguous. The issue arises immediately in the first line of “Leaves of Grass”: I celebrate myself, and sing myself, And what I assume you shall assume, For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

“There’s the ‘you’ that is a whisper to a lover or the ‘you’ that is addressing a crowd,” says Folsom. “Whitman simultaneously speaks to everyone who reads the book and to an intimate single reader, to only you.”

The translator’s choice can often be understood contextually. When readers compare the dozens of translations of “Poets to Come” that the group amassed, suddenly the divergences between a 1933 German translation and a 1990 Brazilian translation leap into relief through the historic lens provided by this section of The Whitman Archive.

Laying Groundwork for Future Translation Projects

The methodology established during the Obermann Summer Seminar proved so useful that it was adopted last summer during the graduate seminar component of the annual International Whitman Week, hosted by the Transatlantic Whitman Association. Students, who come from all over Europe, North and South America, Japan, and India, participated in daily translation sessions modeled on the summer seminar. Another seminar participant, Marta Skwara of the University of Szczecin, is utilizing the methodology the group developed in the seminar as she edits a series of translations and scholarly essays from 12 different countries on Whitman’s famous “barbaric yawp.”

Fortunately for scholars of Whitman, poetry, and the field of translation studies, the collected translations, along with short, illuminating essays by the seminar participants and an introduction by Ed Folsom, have been published as part of The Whitman Archive. This section of the ever-expanding online project, says Folsom, is the foundation for translations to come.

The portrait above is a 1978 sketch by the Uruguayan artist-translator Pablo Mañé Garzón imagining Whitman as a Spanish don.