On February 24, three University of Iowa History PhD alumni visited campus to share their current work beyond academe. All three are exemplary scholars who have earned national and campus recognition for their work. In addition to the acclaim they’ve received, what makes these alumni stand out is their work in the public sector:

- Karen Christianson, whose dissertation explored gender relations in a twelfth-century French monastic community, is the Director of Public Engagement at the Newberry Library.

- Sylvea Hollis, whose dissertation examined an African American fraternal order’s civic contributions following the Civil War, is a National Park Service Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow in Gender and Sexuality Equality.

- Eric Zimmer, whose dissertation explored the sovereignty of the Meskwaki Nation, is a Senior Historian with Vantage Point Historical Services, a private consulting firm.

The Mellon-funded Humanities for the Public Good project, in conjunction with the UI History Department and the collaborators who support the grant—the Obermann Center for Advanced Studies, the Graduate College, and the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences—brought the trio to campus to learn more about their career trajectories. Audio of their talks will soon be available on the HPG website. Here's a snapshot of the exciting work in which the three are currently involved.

Karen Christianson

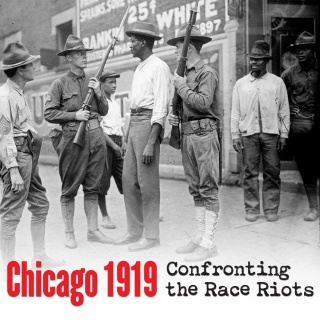

Chicago's 1919 race riots, which were sparked by the murder of an African American man whose raft floated over an imaginary line separating white and black beaches, are no longer part of the city’s collective memory. “As a Renaissance historian, I knew nothing about it,” says Karen Christianson—and it turns out that she was hardly alone.

Following the riots, a 600-page report was written by an extraordinary cross-racial collaborative team. It identified root causes behind the violent events, including the attitudes of the police and the city’s extreme segregation. The report was subsequently buried, and although its findings and recommendations are applicable to the current moment, few Chicagoans know of the riots or their aftermath. Thinking that the centennial anniversary would be a good time to bring this event back into the public’s consciousness, Christianson contacted other historical institutions to learn what they were doing to commemorate the event. But no one had plans.

With Christianson at the helm, fourteen organizations came together to plan and execute a yearlong initiative aimed at raising awareness of the events of that hot and bloody 1919 summer. A major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities funded public events that included youth spoken-word performances and a bike tour of some of the sites related to the riot. Institutional partners included museums and archival organizations, as well as a nonprofit media cooperative and a community bike shop. Christianson is especially pleased that those who shared their expertise and provided context during the commemorative events included both scholars from Chicago universities and community members, including the pastor of a church located in the area most affected by the riots.

Their goal was to bring the 1919 race riots into social consciousness while also using them to discuss current racial issues in the city. The project clearly demonstrates the profound impact of providing a deep, expansive, multi-voiced history for communities that are serious about understanding the local meaning and continuing effects of racism. That knowledge will be carried forward to future generations through a new curriculum about the events of 1919 now being developed for Chicago’s public schools. Meanwhile, the project was awarded the prestigious 2020 Outstanding Public History Project designation by the National Council on Public History.

Sylvea Hollis

In 2011, a report produced by the Organization of American Historians declared that the National Park Service (NPS), which interprets some of the most powerful and instructive historic places in the nation for millions of annual visitors, suffered from “weak support for its history workforce” and had “narrow and static conceptions of history’s scope.” The report, Imperiled Promise: The State of History in the National Park Service, was a wake-up call for the agency to “recommit to history as one of its core purposes.”

The report inspired a relationship between the NPS and the American History Association, as well as the formation of a new program, the National Park Service Mellon Humanities Fellowship. Sylvea Hollis is now midway into a three-year fellowship dedicated to documenting the ways gender and sexuality fit into the history of sites managed by the National Park Service. One of her first projects focused particularly on the Stonewall National Monument in New York City's Greenwich Village and the Women’s Rights National Park in Seneca Falls, NY.

Hollis's experience with the Stonewall National Monument is an example of the many kinds of work involved in public history projects. “It is really on-the-ground, community work,” says Hollis, who went into graduate school knowing that she did not plan to work in the academy. From the beginning, her goal was to be directly involved with historical sites and their surrounding communities. For the Stonewall project, she partnered with neighborhood groups surrounding the site, a nonprofit called Stonewall at 50, and the American History Association’s LGBTQ committee.

Hollis helped to develop the foundational NPS document for the monument; this is the document that specifies which stories will be researched and shared at a given site. Currently, she is part of an oral history project that is intended to reorient the Stonewall riots to the temporal center of the historical arc of queer history. “The riots did not start the queer history movement,” she says. “They allowed for the gay liberation front do the work that we now recognize the results of.” Her work is an important reminder that the National Park Service has a critical role to play in preserving urban histories as well as natural treasures.

Eric Zimmer

How do you capture the wisdom and stories of senior figures in one of the most influential American philanthropies? How does the history of a single Jewish businessman in a rural area become the lens through which to tell the history of an entire community? What technological and storytelling devices can be used to capture the work of a California family foundation that intends to spend down its funds and dissolve but wants to share its knowledge before it does so?

These questions are central to Eric Zimmer’s work with the historical consulting firm Vantage Point, which helps organizations harness the power of their histories. In addition to producing a variety of book-length biographies and corporate histories, Zimmer and his colleagues complete strategic planning and archival assessments for nonprofit and for-profit institutions, collect oral histories, and design public exhibitions.

While Zimmer travels widely for his work, he has intentionally chosen to live in his hometown of Rapid City, South Dakota, where he is active in multiple history-centered projects, including serving as a research fellow at the Center for American Indian Research and Native Studies on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and acting as a project historian for the Rapid City Indian Lands Project.

The latter project grew out of a group of elder Native American women coming to Rapid City and demanding the bodies of Native American children who died when they were forced to attend a boarding school. Zimmer says there has been near total erasure of the story from the community’s memory, even though the echoes of this injustice remain strong through other present-day practices and policies, including the current redlining of Native American communities. Zimmer and other project members are proposing potential land swaps to benefit the Native American community for the land that was illegally transferred.

Give public history a more central place at the table

Karen Christianson, Sylvea Hollis, and Eric Zimmer all clearly delight in doing history in and with the public, applying their scholarly skills to topics and projects that have immediate impact on the many communities and organizations that seek out these impressive historians. They note that the rigorous training they received from the University of Iowa Department of History allows them to provide a quality of research that wouldn’t be possible without their advanced training. At the same time, they would like to see the work of public historians gain a more central place in the curriculum and reward systems of universities.

“Most public history is place-based,” says Zimmer, a fact that resonates strongly with Christianson’s Chicago 1919 project and Hollis’s work at Stonewall. That means public historians must learn to navigate unusually complex and demanding intellectual commitments. Like more traditional academic historians, they must be deeply knowledgeable about their specific historical period, often with a focus on a particular nation or world location; and they must be skilled at mobilizing and interpreting archives, documents of all kinds, and material culture. But they must also be thoughtful, sensitive facilitators and consensus builders who can manage complicated partnerships while remaining open to challenges from diverse communities.

Even the few examples above offer insight into the value of public historians’ work. Christianson helped members of her community unearth painful stories of past racial violence. Then she and her partners pivoted to the kinds of honest conversations about race that offer hope for a more just future. Hollis and her collaborators are re-imagining what being “American” means—opening space for the histories of women and LGBTQ citizens within that most American of institutions, the National Park Service. And Zimmer and his team are using archives and evidence to convince corporations, philanthropic organizations, and nonprofits that, in the long run, telling a full history—mistakes and all—is ultimately the best way to win public trust. The commitment of these three scholars to the ideals of community engagement, social justice, and the infusion of humanities values and methods into civic culture is central to the emerging vision of the Humanities for the Public Good graduate degree.