How do you write down a dance? To capture the body’s expressions, scholars have long turned to Kinetography Laban, a system for recording and analyzing movement that uses abstract symbols to define the direction of movement and the parts of the body that perform it, among other parameters. But what happens when that language of symbols is itself a historical artifact, reflecting the biases of its time? Can a system built on a specific vision of the body ever truly capture the full diversity of human movement, or does it inevitably shape what it records? This is the critical and creative realm of Jordan Gigout, a dancer and dance-notation scholar from Essen, Germany, currently studying at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris. His research explores how this historical language for movement can continue to evolve and inspire new ways of thinking about choreography today. This fall, we welcomed him as an Obermann International Fellow.

“At first, I thought dance notation would let me crack the code of choreography,” Jordan recalls. “But I realized it only revealed one aspect.” That realization became the foundation for his current approach: exploring how notation can be used within choreography, not just after it. “It’s about what the system uncovers, what it allows me to analyze, and what I could not see as only a dancer.”

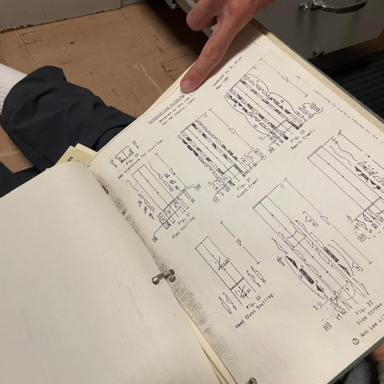

Gigout’s research delves into the complex history of Kinetography Laban, created a century ago by the Austro-Hungarian dance artist, choreographer, and movement theorist Rudolf Laban. While the system gave dance a new materiality and elevated its standing among other arts, its foundation reflects the biases of its time. “The 120-year-old system reflects a vision that was sexist, ableist, and racist: the dancing body is defined as a right-handed, thin, white person,” he says. “But every notation system reflects the time and culture in which it was created.” While the early 20th-century framework mirrored certain social biases, the system remains a powerful tool for recording and analyzing movement. Jordan approaches these aspects as historical conditions to be questioned, expanded, and reimagined. “Learning the system made me question how it was shaping me,” he says. “It doesn’t just record movement—it changes how we think and move. In that way, we transform it as much as it transforms us.”

Kineography Laban has continued to evolve through the people who use it,” he explains. Now, inspired by figures like Irmgard Bartenieff, who adapted and expanded Laban’s theories in the United States, Jordan is exploring how the system can engage with feminist and other critical perspectives. During his time in the U.S., he was deeply influenced by choreographer Annie-B Parson, whose book Drawing the Surface of Dance: A Biography in Charts treats the page itself as a choreographic site. Approaching notation through feminist and critical thought, Jordan treats it as a space for inquiry, asking: “How can we tell stories with dance notation?”

The fellowship also sharpened his reflections on the distinction between choreography and dance. “Annie-B Parson writes that choreography is more perishable than dancing, and dance more perishable than fruit,” he notes. “That line struck me—choreography and dance are not synonymous. I now want to search for ways of writing that honor that complexity."

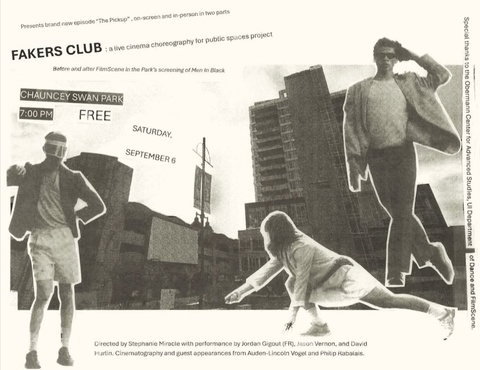

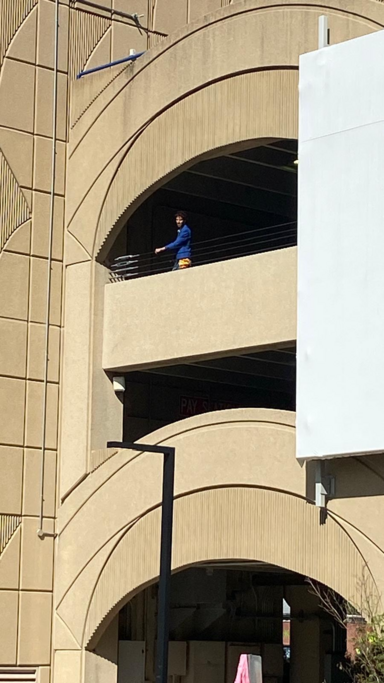

He was brought to Iowa by his friend and collaborator, UI Assistant Professor Stephanie Miracle, to co-create a public performance combining live dance, film, and live music. “It was a beautiful opportunity to collaborate again with an amazing artist I deeply respect—someone who always makes me think and be better,” says Gigout. The September 6 performance took place during a FilmScene at the Park screening, where Jordan, Stephanie, and Jason Vernon performed in front of a film created by Iowa City videomakers Auden Lincoln-Vogel and Philip Rabalais, accompanied by live music from David Hurlin.

It was a resounding success. “It’s a great venue that attracts a diverse crowd, likely including many people who don’t often go to the theater to watch contemporary dance.” The performance aligned perfectly with the mission of the FAKERS CLUB, Miracle’s international ensemble, which aims to make contemporary dance accessible to everyone by using public spaces.

Reflecting on his time at the University of Iowa, Jordan highlights the invaluable support and the connections he made. “Constantly interacting with people outside dance notation forced me to explain my work, which meant I had to find the words and define what I do,” he says. “In my Paris bubble, everyone already knows the system. Here, I met curious and engaged artists who brought other forms of knowledge. That friction was deeply nourishing.”

Jordan gave multiple workshops in the UI Dance Department—exploring dance notation in choreography, functional anatomy, and music classes—while also teaching movement classes informed by his European performance background. “Suddenly, I was wearing the other pair of shoes.” This challenge prompted him to reflect on his own, sometimes traumatic, dance education. “I realized that while I didn’t always agree with the methods some teachers used, the knowledge itself was still valuable. How can I keep the material but change the delivery? The students were so open and curious. I learned as much from them as they did from me.”

A major highlight was the chance to work with the renowned Trisha Brown Company, which was in residence during his stay. “One of the teachers, Melinda Jean Myers, was reconstructing a piece and invited me to the rehearsals so I could practice dance notation,” he shares. “It was an amazing experience to be present in the rehearsal room, practicing my craft with one of the most influential dance companies in the U.S.”

Over time, Jordan’s research evolved into a profound ethical inquiry. “Because notation is an archival practice, it matters deeply how we choose to write and record pieces,” he explains. “I suddenly realized I was holding the power to shape what will be remembered. What do I choose to record, and what gets left out?”

This shift has reframed his work, positioning him as someone who is, in a way, writing history. “It brings to mind a quote from Donna Haraway: ‘It matters what we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.’ I love that idea—it reminds me that the stories and tools we use to describe the world don’t stand apart from it; they participate in shaping it,” he explains. “If we keep repeating the same narratives, we close off other ways of knowing. If we always feed people the same stories, it becomes very difficult for them to see anything else that exists around them.”

For Jordan, notation has also become a way to reclaim artistic freedom, and to listen differently to what moves through him. “Traditional dance training can be very silent,” he says. “A teacher shows you something, and you just copy. At some point, I realized I was carrying unnamed movements that weren’t entirely mine—gestures inherited through lineages, techniques, even ideologies.” He describes this realization as both unsettling and liberating. “Notation allows me to look at these traces without judgment,” he explains. “It’s a way to translate, to speak with the ghostly parts of myself—the movements that shaped me, the dances that still live inside me.” He likens this to an act of correspondence: a language written in the space between memory and motion. “When you read a score, the piece of paper doesn’t talk; it won’t tell you if you’re doing something wrong,” he explains. “The notation itself is about asking questions, and if you follow those questions, the rest is a conversation with yourself.”

He sees enormous potential in notation to democratize dance, giving broader access to choreography’s legacy. “I’m really jealous of musicians. As soon as you can read a score, you can access masterpieces,” he says. “In dance, we face gatekeeping. To dance certain pieces, you have to be cast, which means you need to have the ‘right body.’ Why can’t I learn choreographies just to have them in my body, to become a living archive? If we take the time to write dances down, anyone can learn them. I can dance a version of The Rite of Spring in my kitchen and be happy—for the beauty of the art."

Looking back, Jordan describes the fellowship as a transformative experience. “It gave me time and space to find direction and confidence in my work,” he reflects. “It connected me to artists and thinkers who are inventing new ways of writing choreography into the world.”

Gigout says he “would absolutely recommend an international fellowship,” adding, “It is a unique chance to expand your research network, gain fresh perspectives, and engage with world-class scholars.” He encourages future fellows to immerse themselves completely. “I decided not to travel elsewhere because I wanted to be completely present here. That made the experience incredibly rich,” he says. “As a student in Germany, I learned about the history of modern dance in the U.S. To think that ten years later I’d be in Iowa, working with amazing artists, teachers, and students—it’s truly a privilege.”