A wonderful aspect of the Obermann Center is the way in which people from across the University meet and have unexpected conversations. While many of our programs invite people to form unique collaborations to achieve a specific outcome, such as publishing an article or developing a grant application, our longest running program, the Fellows-in-Residence, is intended to support individual projects. Spending time in the house together for several months, sharing coffee in the kitchen, and meeting in the bi-weekly seminar, however, the Fellows often find connections between each other’s work.

This fall, Professors Stephen Berry (Journalism & Mass Communication) and Jacki Thompson Rand (History) discovered that they were both working on issues of race in the latter half of the 20th-century American South. Berry is writing a biography of Harry Scott Ashmore, the nationally known liberal southern editor of the Arkansas Gazette who won the Pulitzer Prize for editorials challenging segregationist Governor Orval Faubus’ effort to block the desegregation of Central High School in 1957. Rand is researching community violence among the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians in the context of the federal Indian self-determination policy era. In particular, she is trying to reconstruct the history of the rape of a young Choctaw girl, a case that was prosecuted in the Neshoba County Circuit Court in 1972.

The impact of white supremacy is a thread in both of their projects. We invited Berry and Rand to explore this thread via an email conversation, which they have generously shared with us.

The Persistence of White Supremacist Notions

Rand: One of the ways in which our work intersects or speaks to each other is around the subject of white supremacy. My work in Neshoba County is revealing the extent to which southern white supremacist ideologies and the extensively organized KKK affected Mississippi Choctaws. I'm beginning to learn that white supremacy was not exclusively about black and white race relations. Mississippi Choctaws contended with more than simple white hatred of Indians that you find in, for example, South Dakota. It was a hatred that shot through a particular idea of racial hierarchy.

Berry: That’s a good beginning, Jacki. It gets right to the heart of the matter. I firmly agree that white supremacy is one – and perhaps the fundamental and all-encompassing – commonality in our work. I also hope we can explore the ground-level manifestations of “racial hierarchy” that governed black-white and Indian-white relations.

But first, I want to get a little more specific about white supremacy. Regardless of whether we are talking about Neshoba County whites and Choctaw Indians in Mississippi or about the southern whites generally and African-Americans, we have recognized that ignorance, fear, prejudice and lack of association among different races are root causes of white supremacy. However, I am curious about whether you are seeing any circumstances, events, a trend or other concrete factors related directly to relations between Neshoba County whites and Choctaw Indians that help explain the persistence of white supremacist notions there, despite the fact that even by the 1950s it had been soundly and scientifically discredited?

For example, I have been reading research that says in the South as a region, to understand the relevant factors that help explain the persistence of white supremacy vis-à-vis African-Americans one must understand the circumstances that forced African people into slavery, followed by centuries under the dehumanizing conditions of a slave society and its progeny – a share-cropping agricultural system, disfranchisement, and Jim Crow laws buttressed by extra-legal social parameters and rules of etiquette that continued through the mid-1960s. Those peculiarly southern institutions and accompanying rules of behavior, which were enforced by violence or fear of violence, created conduct, behaviors, educational levels, labor, and economic circumstances among African-Americans that white Americans then misinterpreted as affirmative, observable evidence in daily life of black inferiority and white supremacy, which in turn justified continued white dominance.

Reinforcing the Chocktaws' Marginalization

Rand: Choctaws who remained in Mississippi after removal appear to have escaped slavery. They supported themselves by hiring out as day labor and, after settling on marginal (swamp) lands, subsisted by hunting, fishing, gathering, and gardening where possible. But they did not escape other oppressive southern institutions. Once southern whites turned their attention to marginal lands following the Civil War, the Choctaws were pressured to find alternative resources. They entered the sharecropping system, which, as you know, was another form of slavery. All of this reinforced the Choctaws’ isolation, social and economic marginalization, and political powerlessness, particularly since they had been stripped of tribal status.

Throughout the 19th century it is clear that the Choctaws had been categorized as an inferior race akin to African Americans. They would have come under the post-slavery criminalization of vagrancy, I suspect, which was one way of preserving the labor force. Choctaws were prohibited from attending public schools. Without economic power, and without tribal status, they had no political power. Most spoke Choctaw as the first language. They were incredibly poor.

By the 1970s Choctaws were just beginning to emerge from sharecropping, but the isolation and marginalization was very persistent. As more than one person has told me, “First you had the white people, then the blacks, then the Choctaw dogs, and then the Choctaws.” That was the racial hierarchy for Choctaws in Mississippi. Although you can find racism against American Indians everywhere, including in the national discourse, this is different from say, the Plains or Oklahoma, as far as I can tell.

Potential Alliance

Berry: Did that hierarchy apply only to Choctaws’ relationship with whites and African-Americans in Mississippi or to most American Indian tribes throughout the country? That Indian-white racial hierarchy – even if it applied only to Choctaws – is fascinating, perhaps even counterintuitive, in my opinion. Despite the vastly different histories before the 20th century, African-Americans and American Indians suffered extraordinarily inhumane treatment from white people from then on. African-Americans and Indians theoretically had full citizenship rights by then, yet both were treated as inferior under white supremacy and were subjected to discriminatory laws and social policies. It would seem such circumstances – despite the different histories and cultures – would form the basis for cooperation and interaction against common problems, maybe even a political alliance of the oppressed.

Throughout history, different groups, factions, even long-term enemies, commonly formed ad hoc alliances to confront a common foe. Remember how the Populists once tried to form an alliance with African-Americans? During the period that you are studying – the early 1970s – was there any evidence of Indian/African-American cooperation? Or did they eye each other as competitors for jobs? Of course, I can’t help but recall how poor whites reacted to their inferior status vis-à-vis middle and upper-income whites in the South – they became the most devoted believers in white supremacy, the most susceptible to racist demagoguery and the usual participants in lynchings, the rank-and-file and leadership of the 20th century KKK membership and the 1950s segregationist mobs against integration. So, did African-Americans in Neshoba County react similarly to the lower-status Choctaw Indians?

"We think we 'know' a history ... but our knowledge is frequently partial."

Rand: My research doesn’t focus on the African-American community so I’m not in a position to address that particular question, though it appears that African Americans and Mississippi Choctaws never pursued any kind of political alliance. Neshoba blacks and whites formed a committee on race relations in the late 1960s that focused solely on black-white relations. There is no reference to the Choctaws.

Meanwhile, the Choctaw political leadership had devoted their energies to exploiting the War on Poverty programs and the slow turn toward a federal Indian policy of “development.” That policy, which signaled the end of tribal termination under the Kennedy administration, evolved into the federal policy of self-determination that was codified in 1975. Self-determination rested in part on a policy of economic development. The tribal leaders clearly believed that economic development was the ticket to equality for Choctaws and, simultaneously, autonomy. Natives have never been interested in integration, which, as you know, was central to the civil rights project. They are focused on tribal sovereignty, which is in part the focus of my work.

What fascinates me as an historian is that we think we “know” a history, in this case the history of the 20th-century Deep South, but our knowledge is frequently partial. Similarly, your work is revealing that the “liberal” or “progressive” southerner’s narrative deserves closer scrutiny.

The Role of Journalists

Berry: Your observation that “our knowledge (of history) is frequently partial” resonates with my study of white southern liberal journalists in the early years of the Civil Rights Movement. My perspective as a journalist and as a student of race relations history is prompting questions that I don’t think have been addressed in the historical studies of these men. Southern liberal journalists understood that the overwhelming majority of blacks saw integration as a means to gaining their constitutional rights. They realized that post-World War II black militancy was gaining support among the black population. Yet, while advocating equal rights for blacks, these “liberal” editors equated black militancy with White Citizen Council extremism and supported segregation, knowing its progeny included the evils they claimed to oppose.

Historians – generally – have reported that the editors juggled these seemingly contradictory streams of thought in deference to pragmatism, reality and, most importantly, Southern folkways, all of which created their fear of “getting ahead of the community” and the resultant liberalism of gradualism. Historians treat these men as political players. But, I am beginning to think that historians forget that these men, first and foremost, were journalists, which calls into play a new set of evaluative parameters. From a politicians’ perspective, the rationale for gradualism seems sufficient considering the pro-segregation public opinion at the time. But how would that rationale measure up if considered in conjunction with what the application journalistic ethics and performance standards require?

The fundamental charge to journalists has always been “to seek the truth and report it.” Journalists have followed the immortal words of Adolph Ochs, New York Times publisher from 1896-1935, that journalists must report the facts “without fear or favor.” That means they must consider all sides of issues and report what they find without regard for political consequences, including fear of public reaction. Would such demands require them to consider the perspective of segregation’s victims? Would they then reconsider their common use of the word “extremist” to describe black militants, who had grown impatient with Southern white folkways that deny basic human rights to an entire race? From that perspective, would those Southern folkways begin to appear more extreme than black militants who, with the law now on their side, demanded a speedy end to de jure segregation? Such questions suggest a study of liberal white editors’ segregation policy from the perspective of journalist-historian would help flesh out the “partial history” of southern liberal journalist.

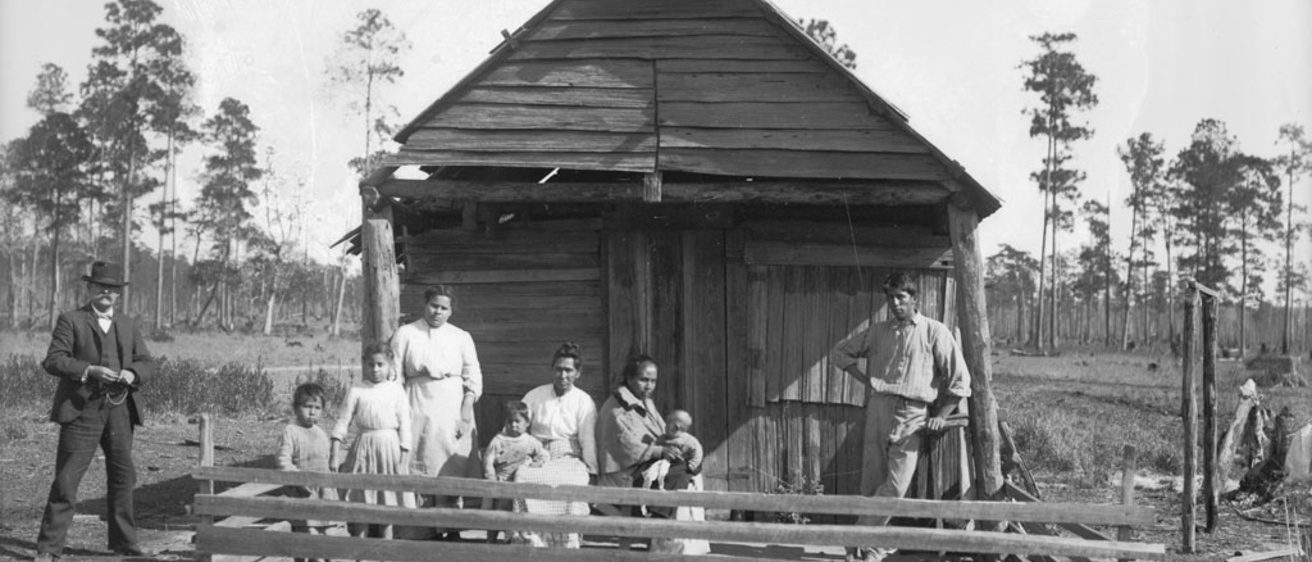

Photograph of Choctaws in Mississippi or Louisiana, collected by National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Museum Support Center.