In a 1949 poem, Gwendolyn Brooks asked, “What shall I give my children? . . . / Who are adjudged the leastwise of the land . . . ” The question is central to Michael Hill’s new book, A Little Child Shall Lead Them: Adolescence in African American Novels, 1941-2008.

Hill, a University of Iowa professor of English and African American Studies and Fall 2014 Obermann Fellow in Residence, is curious about how black communities see their children, especially during the civil rights movement and afterward, and especially the children who are, in Brooks’s words, the “leastwise.” The question arises from Hill’s own experience as a student in the 1980s and ’90s, when academics were turning their attention to black children and women in the context of slavery in works such as Wilma King’s Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in Nineteenth-Century America. At the same time, contemporary images and conversation around black youth centered on teen pregnancy, notably Nancy Reagan’s “Just say no” campaign, and the violent outburst of L.A. street gangs.

The Distance Between Slavery and Rap

These images did not square with Hill’s own experience of black youth culture. They also raised the question of what happened between slavery and the Crips and the Bloods. “There’s a pretty long gap in between that no one is talking about,” Hill laughingly declares. He finds the trope of the adolescent, especially in lesser-known novels, to be illuminating if we want to understand the multiple black reactions to the dominant culture that emerged in the 1950s and beyond.

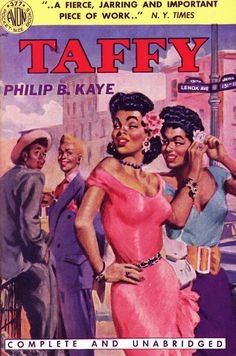

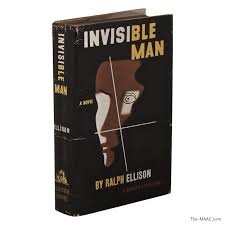

For many readers, post World War II African American literature brings to mind a small cadre of authors, including Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, and James Baldwin, while mention of post-World War II teenage culture evokes Elvis, James Dean, and Holden Caulfield. But instead of Invisible Man, Hill is considering novels like Taffy. And instead of Bigger Thomas, he is focusing on characters like Johnny Johnson, the 14-year-old protagonist of William Demby’s Beetlecreek.

These are books Hill believes scholars, critics, and fellow writers have too long ignored in lieu of relying on a small, established canon. And that’s to the detriment of the larger understanding of the evolution of African American culture.

Adolescence as a Trope for Interpreting African American Culture

“If you follow the children from the 1940s forward,” he says, “you see the possibilities that have been exercised in the post-civil rights era; you can predict the problems that were going to erupt; you can see how things have been conventionalized and appropriated.”

Why adolescents? Socio-historians have suggested that following World War II, the United States was in a period of adolescence. Our infancy was over, and we were now ready for the next steps toward adulthood. It was a period of growth and possibility. But when the same metaphor of adolescence is applied to black culture, it’s a way to signal a permanent holding pattern or stagnation. The adolescent doesn’t appear to be consistent in black literature—in part, Hill believes, because of the dominant belief that “black culture is infantilized; black people are not ready to take care of themselves.”

While Hill has found numerous examples in which the adolescent metaphor for the United States connotes being “pregnant with possibility,” the meaning is not so positive when applied to African American culture. In 1924, Alain Locke writes about the Harlem Renaissance and calls it an adolescence. In 1950, Locke describes black literature as adolescent. “That’s a twenty-five year gestation!” Hill remarks on the absurd assumption that no growth has occurred in the intervening three decades.

Dusting Off Lesser-Known Novels

In the early chapters of Hill’s project, he concentrates on books in which adolescence is a catalyzing power. These include Mark Kennedy’s The Pecking Order, which talks about sexual initiation and black masculinity, and Demby’s Beetlecreek, which deals with post-industrial communities. In these novels, the seedlings of the Black Power movement are planted as one of many options available to the black community.

In these post-war novels, pluralistic blackness and the nonessentialism that will rise in the 1980s are truly born, comments Hill. While it is tempting to turn blackness into placards and slogans, he believes that the messiness of human existence is much more complicated—“but we scholars rarely want to listen or pay attention long enough to capture it.”

Hill urges that these lesser-known voices, which in later chapters will include A. J. Verdelle, Ntozake Shange, and Randall Kenan, are necessary if we want a fuller portrait of not only African American literature but the larger culture that it represents.

From the Invisible to the Front Page

Returning to that very long gap between slavery and the beginning of of hip hop, Hill offers an impressive statistic: “Between 1950 and 1959, African Americans published 125 novels. To put that number in perspective, remember that from 1853, when the first novel by a black American appeared, to 1949, roughly 180 novels by blacks were published. Thus, the total number of books by black novelists increased almost seventy percent during the 1950s.”

Black people are moving from the place of invisibility that Ellison wrote about in his 1952 masterpiece to a very visible stage. By the time you get to the 1960s, notes Hill, “[invisibility] is no longer the dominant metaphor for black adolescents.” That reality can be seen in Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder and in the victims of the Birmingham Bombing and the participants in the sit-ins. In the present, the slippery conspicuousness of black youth surfaces in figures such as Gabby Douglass, Trayvon Martin, LeBron James, and Beyonce.

Hill observes, “The black adolescent is a weathervane for democracy. If you want to know the prevailing winds of American society, look at what’s going on with black youth.” Thus, to return to Brooks, it may not be what we can give to the children; rather, it may be what prophecy they grant to us.

During his fall Obermann residency, in addition to working on his own book, Michael and his wife, Lena Hill, also completed a draft of their co-edited volume, Invisible Hawkeyes: Iowa, Integration, and the Ellisons, a history of black artists and athletes who studied at the University of Iowa between 1934 and 1968. The book is under contract at University of Iowa Press.