In 1898, soon-to-be U.S. Senator Albert Beveridge (R-Indiana) urged his fellow Congressmen to “administer government” to the “savages and senile peoples” of Puerto Rico, newly acquired by the U.S. “Shall we save them from [possession by other nations],” he cried, “to give them a self-rule of tragedy? It would be like giving a razor to a babe and telling it to shave itself. It would be like giving a typewriter to an Eskimo and telling him to publish one of the great dailies of the world.”

Beveridge’s speech is one of many examples of how the U.S. Congress used imperialist rhetoric in its extended debates over Puerto Rico’s colonial status during the first two decades of American “ownership.” Darrel Wanzer-Serrano (Communication Studies, CLAS), a Fall 2017 Obermann Fellow-in-Residence, is currently researching a book project, Possession: Crafting Americanity in Congressional Debates over Puerto Rico’s Status, 1898–1917. Specifically, he wants to see how policymakers’ colonialist rhetoric helped to shape a U.S. national identity rooted in the possession of other places. Rhetoric that, he contends, informs the federal government’s present-day treatment of Puerto Rico, including its anemic responses to the island’s debt and hurricane crises.

So, what exactly is Puerto Rico?

A colony? A territory? A sovereign? A commonwealth?

Congress has been trying to decide Puerto Rico’s status since Spain ceded the island to the U.S. in 1898 to end the Spanish-American War. Congress formally refers to the island as a territory, a place that “belongs to but is not part of the U.S.” For many, though, “territory” is just a euphemism for “colony.” Although they are U.S. citizens, Puerto Ricans can’t vote in presidential elections or on Congressional legislation. Rather, they’re represented by a non-voting “Resident Commissioner” in the U.S. House. And just last year, the Supreme Court ruled that Puerto Rico can’t use federal bankruptcy laws (e.g., can’t file for Chapter 9) to relieve its $74 billion debt, whereas U.S. states can.

For Wanzer-Serrano, “colony” is spot-on. In fact, he notes, “Puerto Rico is the oldest colony in the world.” Originally inhabited by the Taíno people, the island became a Spanish colony in 1508 and stayed that way until the 1898 Treaty of Paris forced Spain to cede sovereignty over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the U.S.

Linguistic roots of imperialism

Though Wanzer-Serrano is himself second-generation Puerto Rican, his interest in the subject dates to graduate school. “Mom wanted ‘good American boys’; she didn’t teach us Spanish or Puerto Rican history,” he reflects of his family. It was in graduate school that he stumbled upon the Young Lords—a multi-ethnic, grassroots Puerto Rican nationalist group that advocated independence for Puerto Rico. The group quickly became the subject of his dissertation and first book, The New York Young Lords and the Struggle for Liberation (Temple UP, 2015). The book recently received the 2017 Book of the Year Award from the Critical/Cultural Studies Division of the National Communication Association.

What interests him now is how the political rhetoric used in four key Congressional disputes over Puerto Rico helped to shape a particular sense of “Americanity”—an ideology and rhetoric built on the linking together of racism, capitalism, coloniality, and civil religion.

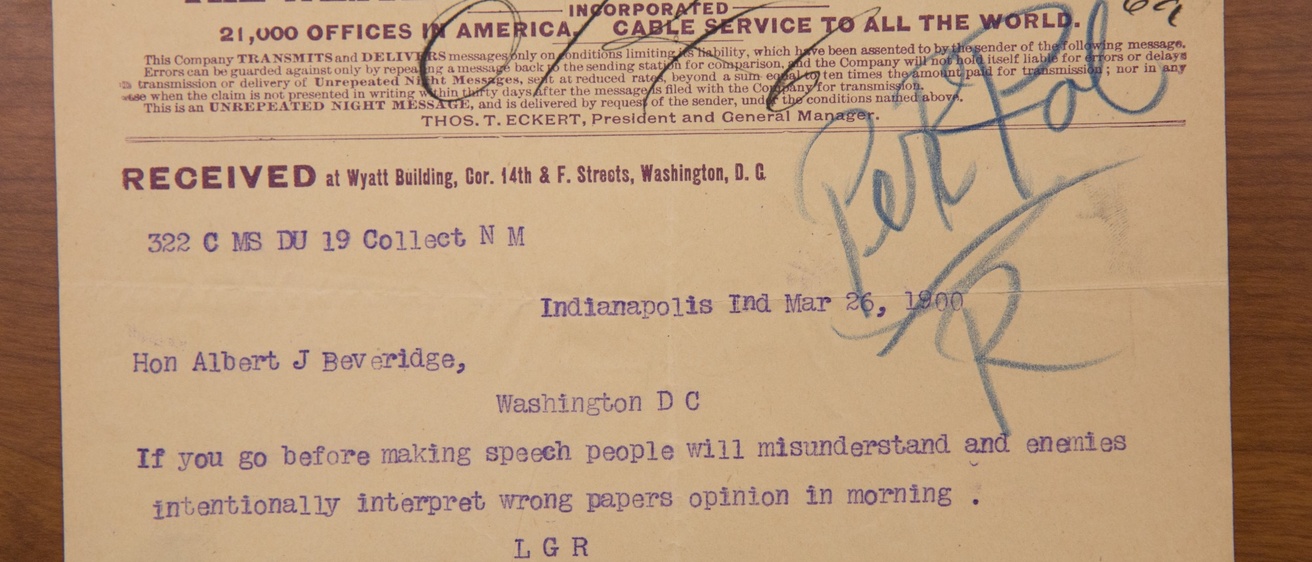

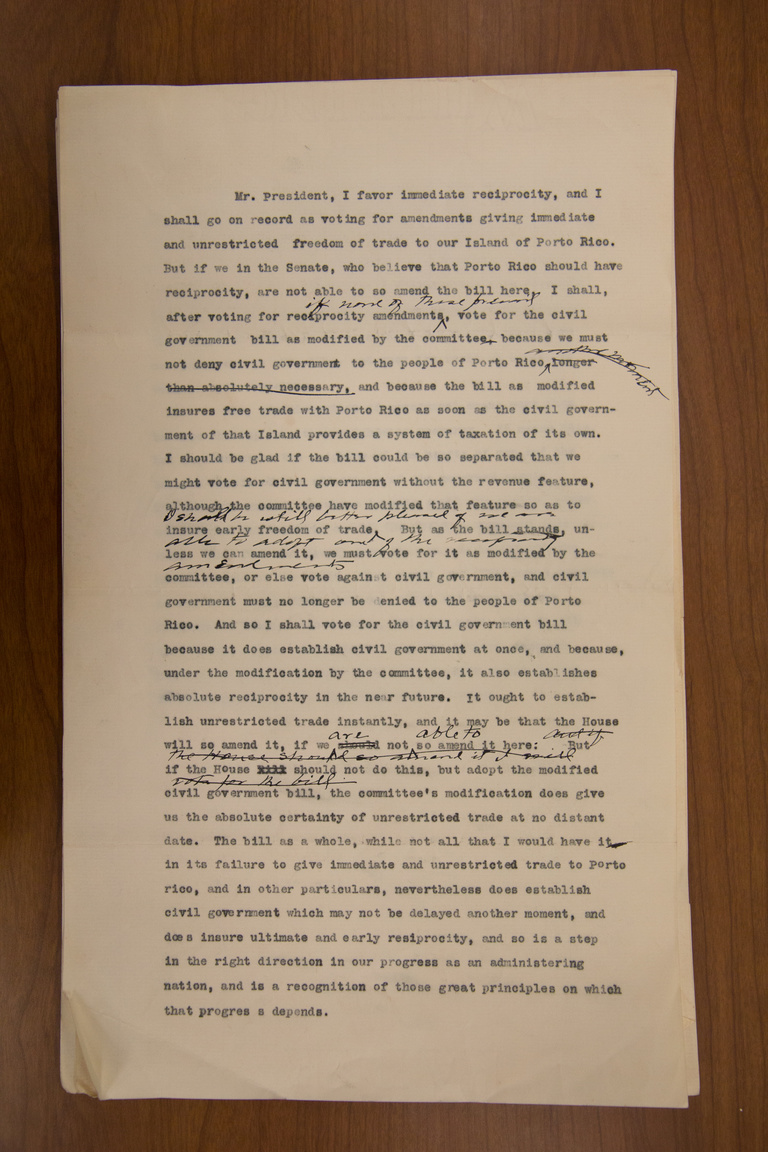

For his new project, Wanzer-Serrano is examining policy debates surrounding the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the Foraker Act of 1900, the Olmsted Amendment of 1909, and the Jones Act of 1917. The research involves digging through Congressional documents, coverage of the debates in the key players’ local papers, diplomatic telegrams from the late 1890s, and archival materials of the Congressmen who proposed and supported each piece of legislation. These records are often hard to come by, since it wasn’t customary for U.S. representatives and senators to preserve documents at that time. A further difficulty, notes Wanzer-Serrano, is that “so much of the legislation was accomplished in back-room dealings, behind closed doors.” The Treaty of Paris, for instance, was ratified by the Senate in an executive session of which no record was kept.

“The juiciest archive is Albert Beveridge’s,” says Wanzer-Serrano. The largest trove of the politician’s papers are in the Library of Congress and include allusions to saving “our race,” as well as to his health issues. “He was a political workhorse who was suffering ‘nervous exhaustion’ for which he had to consume a ‘tonic’ that made him feel ‘full of life, thought, vim and vigor, and look like a race horse,’” says Wanzer-Serrano. “It almost certainly included a hefty dose of cocaine.”

Beveridge was an outspoken American imperialist known for his long, impassioned speeches in support of expanding U.S. territories overseas. His 1898 Indiana Republican Convention speech, known as the “March of the Flag,” was infused with the grandiose rhetoric of Manifest Destiny: “Hawaii is ours; Porto Rico [sic] is to be ours; at the prayer of her people Cuba finally will be ours; in the islands of the East, even to the gates of Asia, coaling stations are to be ours at the very least; the flag of a liberal government is to float over the Philippines, and may it be the banner that Taylor unfurled in Texas and Fremont carried to the coast.”

According to Wanzer-Serrano, the speech “paints an interesting picture of how the U.S. national character, as embodied in the Constitution, requires America—‘the sovereign power of earth,’ according to Beveridge—to take care of Puerto Rico.”

Statehood?

There’s no doubt that 500 years of colonialism have hurt Puerto Rico’s economy and infrastructure, says Wanzer-Serrano, but he doesn’t think conditions will change any time soon: “The U.S. is too invested in maintaining a colonial relationship with Puerto Rico.”

In a recent Obermann Conversation organized in response to Hurricane Maria, Wanzer-Serrano, Alberto Ortiz Diaz (History, CLAS), and Mariola Espinosa (History, CLAS)—all scholars of Puerto Rican descent—agreed that even under Democratic-controlled Congresses, there has been no real interest in addressing Puerto Rico’s current status, thus leaving it in a never-ending, ambiguous hinterland. Possessing the island remains too much of an economic advantage, explains Wanzer-Serrano; it allows U.S. industries (most recently, pharmaceutical giants) to use Puerto Rico as a temporary tax shelter, and it provides a convenient military base and port. All of this allows the U.S. to “project its power” across the world. (For an accessible introduction to the history of Latina/o/x people in the U.S. generally, and of the U.S.-Puerto Rico relationship in particular, Wanzer-Serrano recommends Juan Gonzalez's Harvest of Empire.)

He's in talks with publishers about his current project. “I envision the new book as a prequel, of sorts, to my Young Lords book,” he says. “Where my last book examined the ways one can delink from modernity/coloniality, this new project examines some origins of coloniality in the U.S. context.”

Telegram and manuscript photos are from the Albert Jeremiah Beveridge Papers (MSS12591) in the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.