Twice now, art historian Sarah Kyle has visited the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice to study the Roccabonella Herbal, a fifteenth-century illustrated book of plant medicines. Neither the text of the 900-page volume nor its more than 450 images are available digitally, and Kyle is interested in the interplay of the two.

“Although the book is extremely fragile,” says the associate professor of humanities at the University of Central Oklahoma and a 2017–18 Obermann Fellow, “I’ve been able to persuade the curators that because my project focuses on how readers experienced the book and engaged with it as an object, my research demands seeing the book itself.”

Book of Multiple Mysteries

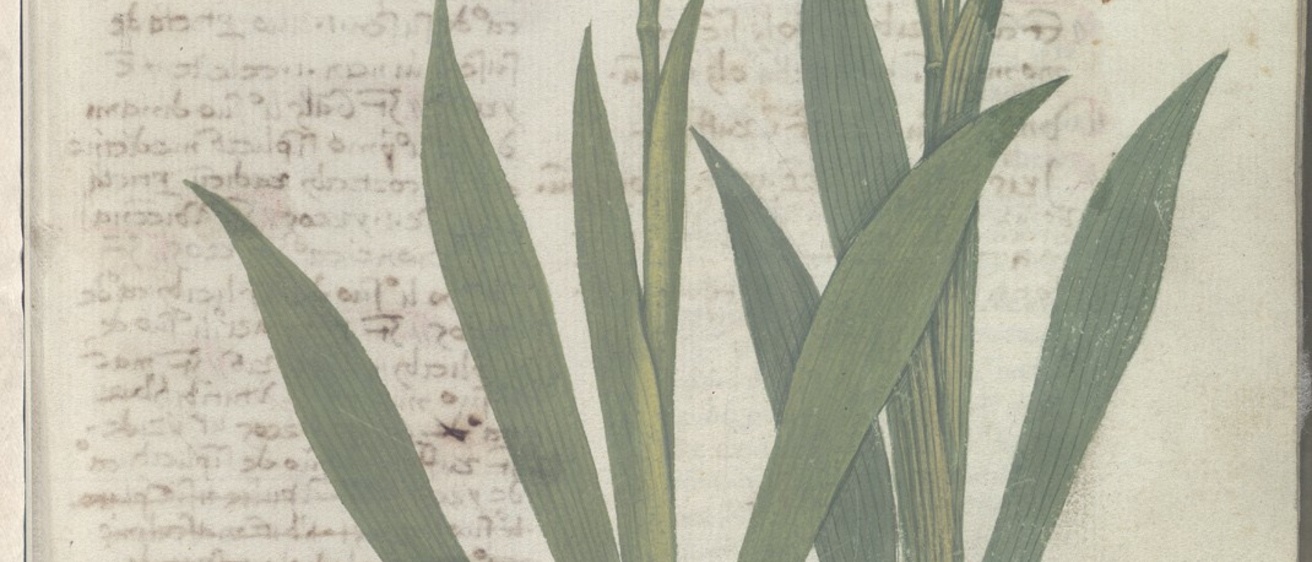

Written by Nicolò Roccabonella, a Paduan physician, and illustrated by Andrea Amadio, the book is particularly fragile because the paintings and handwritten text are on paper, not the more durable vellum (animal skin). Why the book was made of paper is just one of its multiple mysteries. Another is the fact that Roccabonella commissioned the illustrations, which were surely a large investment, but did not pay for a scribe. Instead, he handwrote the text himself, despite his rather poor penmanship.

The book consists of folios, each of which has a full-page illustration of a plant on one side and text on the other that includes a description of that plant’s physical properties; evolving lists of synonyms in several languages, including Latin, Greek, and Arabic; and references to other experts on the plant’s medicinal uses. Although both medical and art historians have taken an interest in Roccabonella’s tome—one group focused on the book’s text and the other on its imagery—Kyle is seeking to understand how the text and images work together.

Medicine and Humanism

She came to the unusual book via a slightly earlier work, the so-called Carrara Herbal, which is the topic of her dissertation and ensuing book, Medicine and Humanism in Late Medieval Italy: the Carrara Herbal in Padua (Routledge, 2017). Containing an Italian translation of a treatise on medical botany written by an Arabic-speaking physician in the mid-thirteenth century, the sumptuously illustrated book was in the collection of the last lord of independent Padua, Francesco Carrara. Kyle’s research on the Carrara Herbal focused on the practices of medicine and humanism that were rising in Padua at that time and the book as a place of cross-pollination.

Intriguingly, Amadio, the illuminator of the Roccabonella Herbal, copied over fifty images from the Carrara Herbal. Although this wasn’t an unusual practice at that time, the mystery lies in how he even saw the Carrara Herbal. “The last record we have for it dates to 1404, when it was in possession of the prince [Carrara]. We don’t know its whereabouts again until the late sixteenth century, when it shows up in the library of a renowned natural historian in Bologna,” says Kyle, adding, “What I wouldn’t give to know where it was in between!”

Today, the Carrara Herbal is in the British Library, and like the Roccabonella Herbal, Kyle says it represents a “network that maps relationships between artists, physicians, and the developing study of botany.”

Retracing a Journey

In an era prior to the printing press, illustrated books were often expensive and time-consuming to produce. Their manufacture reflected the values of both the makers and patrons who created and collected them. The journey of the Roccabonella Herbal from its collaborative creation to its use and later collection by scholars and pharmacists interests Kyle. “I want to chart the authorship and what happened to the book before it was put into an institutional context in the seventeenth century,” she says.

In his introduction, Roccabonella states that he created the book as a resource for his son, who was in medical school. It also incorporates knowledge from the author’s father, who had been a physician, too. After the death of Roccabonella and his son, however, the book left the family and was displayed in a Venetian pharmacy—perhaps for over fifty years—at a time when pharmacies were spaces for information exchange.

When Roccabonella was creating his book, physicians were generally removed from the medicinal plants themselves. Although physicians might prescribe herbal medicinals, such as chicory for its digestive properties, they couldn’t necessarily identify the plants in nature. Herb gatherers—women and men familiar with oral traditions and trained in an apprentice system—were the ones who identified and located the plants. Traders purchased them from the gatherers and sold them to pharmacists, who then processed them. At the end of this pipeline were the physicians who prescribed them.

Threads of Inspiration

Kyle’s interest in books that were created to collect knowledge of the natural world and its healing properties stems partly from her own background. “The women in my family always had herb gardens,” says the native of Ontario, Canada (who admits to not having inherited a green thumb).

Kyle came to Iowa City this year for her sabbatical leave, and resources at the University of Iowa have been invaluable to her evolving research. The John Martin Rare Book Room in the Hardin Library for Health Sciences, including conversations with archivist Donna Hirst about early medical books, and access to the Center for the Book and its many knowledgeable researchers on the history of paper and book arts have added depth to her project.

As an Obermann Fellow, Kyle says she’s also benefited from conversations with scholars in fields that range from social work to German. “It’s been great to talk across disciplines; the other Fellows ask questions I’d never think to ask,” she says. “It’s really forced me to look at my project with new eyes.”

This summer, Kyle will return to Venice, where she’ll spend time in the local archives researching the book’s later owners and their libraries. Though she will not have her hands directly on the Roccabonella Herbal, it will be wonderful to be in the same town!