Yellow fever was once a terrifying killer that violently took the lives of half of the people who contracted it. It killed workers building canals, soldiers engaged in sieges, and investors on fact-finding missions. A viral disease spread between humans and primates, it is caused by a species of mosquito that prefers clean, fresh water. Before this was proven decisively in 1901, yellow fever was a major player in the Caribbean during the colonial period.

On the street where you live

The virus, which often reached epidemic proportions and was used to stir racist hysteria, has been historian Mariola Espinosa’s research companion for more than two decades. After first concentrating on Cuba, she has broadened her scope to a book project, Fighting Fever in the Caribbean: Medicine and Empire, 1650–1902. Espinosa, an Associate Professor in the Department of History and a Spring 2019 Obermann Fellow-in-Residence, says that her focus on yellow fever occurred greatly by chance. As an undergraduate at Princeton University, she found herself grasping for a topic to research for a history class. The professor was a native of Puerto Rico, as is Espinosa, and he suggested that she research the namesake of the street on which she’d grown up in San Juan: Ashford Avenue.

“It turned out that [Ashford] was a military physician who dedicated his life to understanding and curing tropical diseases,” says Espinosa, who, as a kid, had often walked by the doctor’s house where his widow still lived. “The project placed me in the space in which I’d grown up.”

It also gave her a toehold in the medical world, a place she’d always been close to but resisted. “I come from a family of physicians but have always hated hospitals,” she admits. Medical history became her academic trajectory. The U.S. sanitation campaigns in Puerto Rico were the focus of her senior thesis. For her dissertation at the University of North Carolina, she turned her attention to Cuba, taking on the role of yellow fever in U.S.-Cuban relations: “How do you see colonial power relations through the lens of health?” The resulting book, Epidemic Invasions: Yellow Fever and the Limits of Cuban Independence, 1878–1930, was published in 2009 by the University of Chicago Press.

Yellow fever's power dynamics

As she worked with archival materials—tracking down obscure duplicates of documentation that had been destroyed by the U.S. government when it culled an archive in need of more space—Espinosa discovered that although colonial forces had been “obsessed” with yellow fever, the disease wasn’t even one of the top killers in the region (tuberculosis and enteritis held those mantles). Why all the fuss? Partly, it was a matter of who was getting sick.

It was not just the poor, native populations. Rather, significant numbers of European troops were killed by the disease while trying to recapture various colonies. Some three-fifths of British troops were killed while trying to seize Haiti from France in 1793. And the disease was making its way north. In 1878, an epidemic that began in Mississippi and made its way to Illinois was traced to a ship from Cuba.

“It killed investors, foreign officials, and soldiers,” says Espinosa, “unlike TB, which killed the local population. I didn't need to dig in too much to find the power dynamics in health."

Espinosa was drawn to this “history of humans, microbes, and ideas” because if affected the whole of the Caribbean and provides a vehicle for moving beyond the usual area studies approach in which students of the British Empire, for example, might focus on Jamaica, whereas those with a research focus on the Spanish empire turn their attention to Cuba.

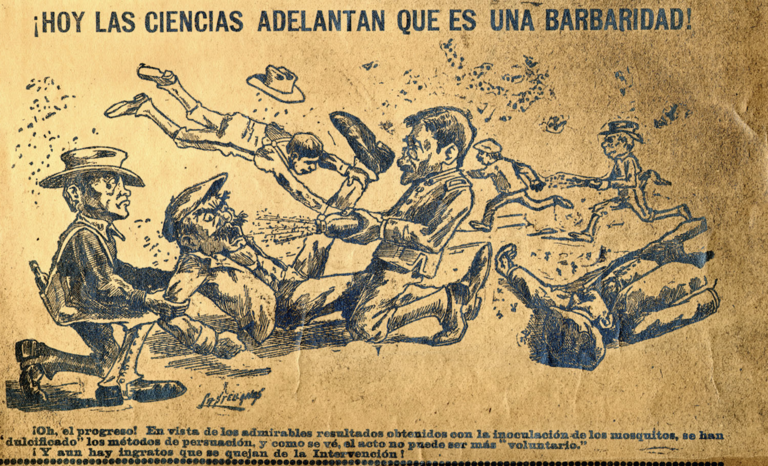

[This political cartoon from the Cuban newspaper La Discusión, August, 1901, reads, “Today the sciences advance so fast it is amazing!” with the subtitle: “Oh! To progress! Seeing the admirable results obtained with mosquito inoculation, they have 'sweetened' the means of persuasion, and, as can be seen, the act cannot be more 'voluntary.' And there are still ingrates that complain about the Intervention!”]

Disregard for national boundaries

One can stand on a mountain in Puerto Rico and see islands that are not part of the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, Espinosa notes, but it took a visit to Saint Thomas, a former Danish colony, to crystallize the idea that “the Caribbean is not bound by imperial and linguistic barriers.” Tuning into radio stations that quickly morphed from French to English to Dutch to Spanish, and meeting people at a wedding who were all resolutely Caribbean and yet had radically different colonial heritages changed her scholarly approach.

“Like maps cropped along national borders,” Espinosa writes in her book proposal, “these works can obscure the interconnections between the islands and the surrounding mainland. … Disease and microbes are not alone in their disregard for national boundaries in the region.”

A fascinating aspect of her current project has been to follow the information trail, especially among physicians and other medical resources. Espinosa has obtained more than 300 primary sources from Britain, France, Spain, the United States, Cuba, Colombia, Haiti, Jamaica, and Mexico, including government documents, memoirs, travel accounts, medical treatises, dissertations, and newspapers.

Scraping archives, mapping data

“Fifteen years ago, I’d have been in a lot of imperial archives. But now I’m following a rabbit hole of sources,” she says. “It's possible to map the transmission of medical knowledge about the disease across time and the borders of the rival empires contesting the Caribbean.”

One can trace, for example, the understanding that yellow fever did not occur at higher elevations—information that shows up in multiple texts published in multiple countries. And yet the information was blindly ignored by British colonial forces during that disastrous attempt to steal Haiti from the French.

In order to fully delve into the region’s patterns of migration, political skirmishes, and transfers of information, Espinosa has relied on digital text-scraping tools, including a text-mining program developed by her husband Frederick Solt, Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Iowa. Via these tools, she has found that "concurrent mentions of race and yellow fever increase over time as empire expands in the Caribbean.”

Some of her digital work on the project was inspired by the 2016 Digital Bridges Summer Institute, “Making Meaning with Data in the Humanities and Social Sciences.” More recently, Espinosa attended the first of several workshops sponsored by the Journal of Social History at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University to begin incorporating a visualization about cross-communication regarding racial immunities to yellow fever into a historical argument.

“I am plotting on a timeline the first time a reference occurs,” she says, “and then subsequent mentions of correlation and whether they are referencing each other.” In addition, although the medical centers during this period were in Edinburgh and Paris, what she’s finding is knowledge produced in Port Au Prince and Barbados—a decentering of Western medical knowledge.

Directing Global Health Studies during research leave

A Career Development Award in the fall and a History Department Mid-Career Research Fellowship this spring have provided Espinosa a large amount of time to focus on her current book project. As the Director of Global Health Studies, however, she has maintained strong connections on campus, overseeing one of the fastest-growing majors at the University of Iowa.

What began nearly 25 years ago as a graduate certificate program became an undergraduate major three years ago. Nationally, Espinosa says, the UI’s program is unusual for being at the intersection of the humanities and social sciences. And it’s thriving; there are currently 126 majors (despite there being only two 50% faculty).

Espinosa stresses that the program is not just about sending students literally and figuratively abroad, but about how global shifts impact Iowa, such as immigration trends and food security. As a native of the Caribbean whose research delves into the effects of empire building on her home, Espinosa is uniquely positioned as a scholar to help students question the relationship between the global and the local.

[About the top image: Street pickers with can carriers in Matanzas, Cuba, from the records of the Military Government of Cuba, US National Archives, College Park, MD]