Imagine if your social stature and your livelihood were dependent on your ability to write poetry and refer to the work of other poets. If there were poetry competitions among the elite that decided one’s worthiness. Or if the entire direction of a nation could be changed via 31 syllables.

Japanese waka, a 31-syllable precursor to haiku, held just this kind of sway for several centuries. Its role in a power play between two imperial factions is at the heart of Kendra Strand’s current book project, An Unfamiliar Place: Poetry, Landscape, and Power in Medieval Japanese Travel Writing. Strand (Asian & Slavic Languages & Literatures, CLAS) is an Obermann Fellow-in-Residence this fall who is focused on three men who were writing between 1350 and 1375 in the Nanbokuchō era: Sōkyū, Nijō Yoshimoto, and Ashikaga Yoshiakira. A Buddhist priest, a statesman, and a shōgun, respectively, these men knew each other and alluded to one another in their writing.

The cultural currency of waka

Of particular interest to Strand are the travel diaries the men kept. These poetic narratives were composed about journeys the writers made throughout Japan during a time when two rival emperors came into direct conflict over the right to rule. Waka, which originated in ancient oral traditions, had become the dominant form of courtly writing by the ninth century. One subset of waka is concerned with celebrating famous places. From a particular mountain’s autumn leaves to a remote plain that once provided the setting for a heroic event, the famous places celebrated in these poems became important travel destinations for centuries, purely for their importance in the poetic canon. Even if the purpose of one's journey was political or military, the traveler would ostensibly stop to compose poems in praise of famous places rather than describe the more mundane aspects of life. And if a place had not already been heralded in an earlier poem or by a famous poet, then it was not worthy of mentioning in one’s own poetry.

The custom was to visit a place and write one’s own waka that clearly referenced the earlier poems, demonstrating one’s familiarity with the canon. One effect of this, says Strand, is that the poems became “ossified” within a literary tradition that values convention and formula over realistic descriptions or new information about a place. The three men’s travel diaries fascinate her because they manipulated this tradition in subtle but telling ways.

“Even if they repeat the classical imagery typically used to describe these famous places, they are making additional comments about what has changed or what is missing,” she notes. “They are pointing to rupture.” The priest, for example, became engrossed in doing anthropological studies of the places he visited, including interviewing local people to confirm whether the things described in earlier waka actually happened. And the statesman abruptly abandoned all mention of famous places and poetry about halfway through his diary, in favor of a fervent prose description of the military conflict that was unfolding before his eyes.

Legitimizing a court in contention

They are also making a case, perhaps subtly to modern readers, for the legitimacy of the Northern Court emperors. While the Northern Court maintained its power by occupying the imperial palace in Kyoto, their rivals to the south in Yoshino produced other symbols of imperial power, including a treatise showing direct lineage from the ancient rulers to the present. One side had a city and a ritual center; the other had documentation of bloodline. In a move that demonstrates the influence of written documents, these three diarists sought to express power by composing poems and demonstrating their connections to important famous places.

Even today, says Strand, the emperors who reigned under the Ashikaga shogunate are generally considered in modern historiography to be illegitimate, as pretenders to the throne. By identifying the dominant rhetorical trends surrounding cases of imperial legitimacy during this time period, Strand is opening new avenues for discussion about how we understand and interpret history today. This is one way that studies about premodern Japan have contemporary relevance, something that has become clear as historians scrambled to find precedents for recent developments surrounding Emperor Akihito’s abdication, including selecting a new era name, Reiwa, and facilitating the accession of Emperor Naruhito (October 22, 2019).

There are major differences in research methodology and theory between scholars of premodern Japan (prior to 1868) and those of the modern era, explains Strand: “It’s one of my major goals to define continuities between the two eras.” Bridging the premodern/modern divide in scholarship was central to the international conference she organized in spring 2019, “Travel Is Home: Travel and Landscape in Japanese Literature, Art, and Culture.” At the event, twenty scholars representing different periods presented their research on the interaction between humans and their environments, including instances of all forms of travel, from evacuation and refuge to pilgrimage and tourism.

A thread throughout Japanese literature is that one’s superior knowledge of the poetic canon, as demonstrated through poetry, calligraphy, and other art forms, lends cultural capital that in turn boosts one’s social and political position. This is certainly the case of Nijō Yoshimoto, the statesman in Strand’s project who was at the center of the conflict between the two rival courts. Although originally of moderate standing in the Southern Court, he leveraged his knowledge of literature and court precedent, along with his skill as a poet, to secure a lofty position in the Northern Court as regent and chief advisor to the young and inexperienced emperor.

A new language of geography

Forced to take to the road during multiple attacks on Kyoto, Yoshimoto’s poetic travel diary describes his expulsion from the capital, his uncertainty on the road, and his eventual joyous return to the palace. How he and other key figures of the Northern Court constructed geography would impact medieval Japanese cultural production for centuries to come, says Strand. “By representing famous landscapes of Japan through a range of media and genres,” she writes, “a cohort of elite warriors and aristocrats developed a new language of geography that they used to demonstrate imperial legitimacy and constitute imaginations of the ‘Japan’ of the day.”

The production of poetry and other art forms, Strand argues, were crucial to a changing nation’s evolving understanding of itself. Both in the north and the south, the elite were producing cultural materials “with the awareness that imperial succession was at stake, and that this was a moment of significant transition in which the most successful and potentially canonical literature would play a part in shaping that.”

So, imagine, again: what if our political world depended on one’s ability to adroitly place 31 syllables? If you think of the power of today’s tweet or other forms of pithy writing, is it so different?

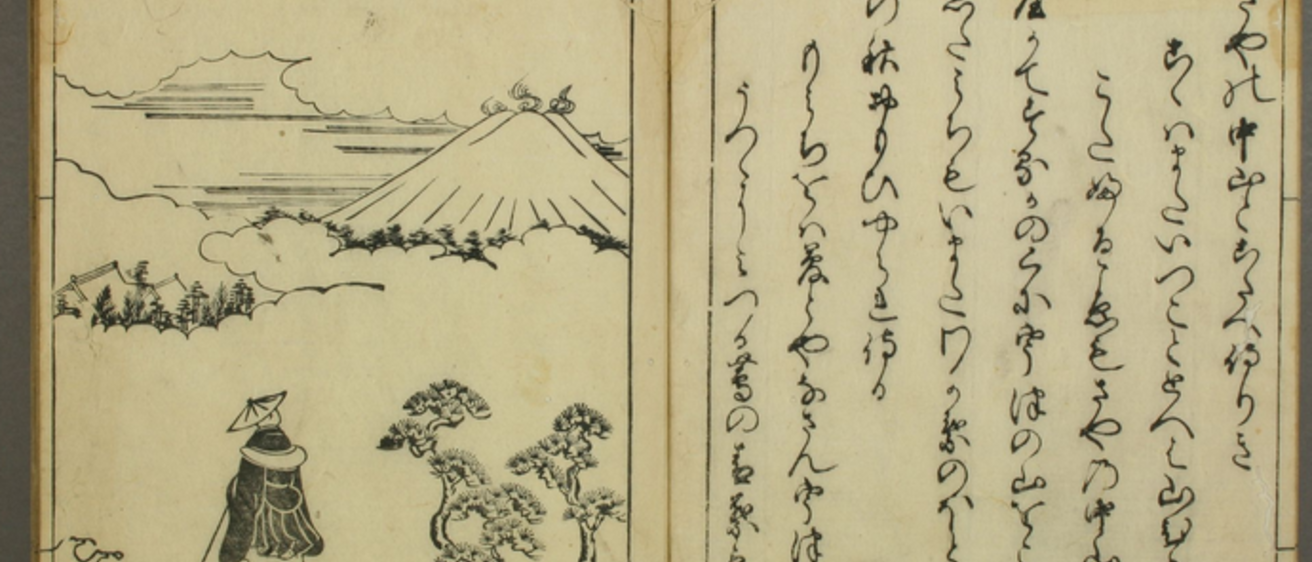

About the image: This two-page spread from a bound printed volume of Sōkyū's travel diary (Souvenirs for the Capital / Miyako no tsuto, ca. 1350) is woodblock print on mulberry paper, printed in 1695, commissioned by Kawakatsu Goroemon, a private bookseller in Kyoto. The script on the right page reproduces the look of a manuscript, while the image on the left illustrates Sōkyū in his humble priest's travel robes, stopping to look up at Mount Fuji in the distance. The image is from Waseda University Library, open access use.