While completing a PhD in Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Iowa, Martín López-Vega took a course on the Golden age of Spanish theater. When the class read Valor, agravio y mujer by Ana Caro, López-Vega was shocked. Though he was a native of Spain and had studied literature at the University of Spain, he’d never before heard of Caro.

The course, which led him to discover the names and works of multiple women authors who had previously been unknown to him, was taught by Ana Rodríguez-Rodríguez. “Her focus was totally innovative for me,” says López-Vega, “as well as contagious. She’s an amazing professor—completely mind-changing.”

Surfacing forgotten female authors

So much so that when López-Vega began working at Spain's Cervantes Institute, first overseeing cultural programming and eventually directing an organization tasked with amplifying Spanish culture throughout the world, he called on Rodríguez. Though she had no previous curatorial experience, López-Vega wanted her to create an exhibit about Caro and other forgotten and overlooked Spanish female authors.

The result was Wise and Valiant: Women and Writing in the Spanish Golden Age (Tan sabia como valerosa: Mujeres y escritura en los Siglos de Oro). The exhibition was on view at Madrid's Cervantes Institute in 2020 and lives on as an award-winning digital exhibition. The title comes from the writings of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, one of the featured writers. The words were an inspiration to Rodríguez, spurring her to tell these forgotten stories and do what she said sometimes felt like “subversive work.”

Rodríguez is familiar to University of Iowa students for her classes about Cervantes’s estimable novel Don Quixote, about which she co-directed the 2015 Obermann Humanities Symposium with Denise Filios. She is also something of a rarity as a researcher and teacher of Spanish literature who also teaches undergraduate language classes. This points to her interest in making literary and scholarly work accessible to wider audiences.

"This work doesn't count!"

Curating the exhibition appealed to Rodríguez for just that reason: it was an opportunity to introduce unheralded writers to the public and to sharpen her own skills at communicating beyond the academy. The project took about two years from when she was invited by López-Vega to the opening in March 2020. During that time, Rodríguez researched the writers, learned about curation, hand-selected objects for display, worked intimately with an exhibit designer, and wrote the text that audiences would ultimately read.

All the while, she admits that there were voices in her head detailing the reasons why a faculty member shouldn’t embark on a two-year voyage like this, reasons any graduate student or faculty member knows all too well: “You should be writing your book! This work doesn’t count!” Indeed, the exhibit took time away from Rodríguez’s current academic research about Spanish writers in the Philippines during Spain's colonial rule of the archipelago. It would have been easy and arguably prudent for her to say no to the Cervantes Institute and stay focused on promotion.

However, she found support and enthusiasm for her decision when she participated in the Obermann Faculty Institute on Engagement and the Academy in January 2020. The four-day workshop provided her with a sense that there is a group of fellow travelers at the University of Iowa who share her dedication to public-facing work, as well as with a host of skills for doing the work effectively and ethically.

“We talked about how to be certain to do work that is mutually beneficial,” she recalls of the readings and conversations. “It was always on my mind while working with the Cervantes Institute. They were spending a great deal of money. How could I make sure they got the exhibition they wanted with my guidance?”

Career highlight

According to López-Vega, familiarizing the public with a group of all-but-lost writers was the Institute's foremost goal. When they hit an early bump because the Institute’s exhibition space in Madrid didn’t have the climate control required to safeguard the centuries-old books, López-Vega and his team raised money to have suitable vitrines constructed. And when Wise and Valiant opened the first week of March 2020, only to have the entire country—including the exhibit space—close down two weeks later due to COVID-19, the exhibition team immediately began working on an online version.

Rodríguez, who grew up in Galicia in northwest Spain, was present for the opening and again for the reopening that occurred in June. Along with the publication of her first book, she says that the exhibit is one of the highlights of her career.

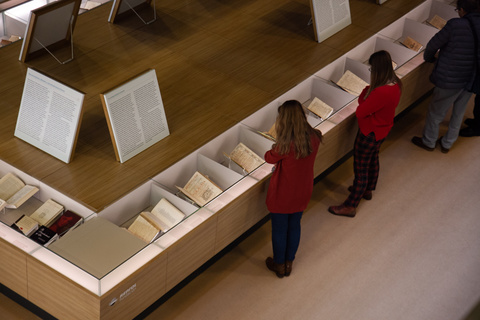

“It’s one thing to be recognized by your academic peers, but to have regular people who don’t know much about the subject get really excited by it is so satisfying,” she says with characteristic ebullience. She admits that on a number of occasions, she quietly visited the exhibit to watch people interact with the materials on display: "Once, there were two high school girls reading the labels, and you could see their reaction: ‘Look at what this lady was doing this in the seventeenth century!’ I could tell that their minds were blown and that they felt so happy and empowered as women.”

She likens the work of writing wall labels as a high form of translation. Not only are the labels very short and necessitate simple language, but, in essence, they were her chance to sell her subjects so that audiences would want to know more. Her greatest hope was that people would leave the exhibit and actually read the women’s work.

Smithsonian's recognition

For all of the homage that Spaniards pay to the literary and other artistic greats of Spain’s Golden Age, Rodríguez finds it frustrating that some of the Age's women writers are so little known: “They are as good if not better than their male counterparts.” While a few have modern readership, including St. Teresa of Ávila, many have gone unrecognized. This includes Ana Caro, a playwright and poet active in the first half of the seventeenth century who was surely among the first women in the world to be paid as a literary figure. Rodríguez edited a new edition of Caro’s book, Valor, agravio y mujer. “There were no available editions,” says López-Vega, “and so Ana prepared the best one to date.”

Rodríguez calls the writers featured in the exhibition “really bad-ass” and hopes they are somehow celebrating their current success. Indeed, they have much to kick up their heels about. In December, the Smithsonian named Wise and Valiant one of the top ten online exhibitions of the year, spurring droves of housebound lovers of culture to visit it. And currently, several high schools in Madrid are using the exhibit materials to teach some of the works featured in it, including Caro's.

Having discovered a new outlet for her research and writing, Rodríguez is dreaming ahead to a possible exhibition about Spanish writers who emigrated to the U.S. after the Spanish Civil War. In the meantime, she has no regrets about her decision to add a new kind of work to her CV: “Maybe it doesn’t count for promotion, but it counts for my satisfaction at the impact of my work in the world.”