“I had to think in images.” This is how Rachel Williams explains her progression as the artist-author of two graphic histories who moved from illustrating the words of others to bringing a story to life on her own terms. A painter and art educator by training, Williams’s approach has always been multi-disciplinary. For her recently published books, Run Home If You Don’t Want to Be Killed: The Detroit Uprising of 1943 and Elegy for Mary Turner: An Illustrated Account of a Lynching, she took on additional roles, including that of historian and archival detective. In the decade-long process, her artistry and scholarship expanded and collided, each serving the other.

Seeking stories

A fan of the journalist-comic artist Joe Sacco, Williams (School of Art & Art History, CLAS) was seeking historical stories that lent themselves to a graphic telling. After a friend encouraged her to look more deeply into the events of Detroit in 1943, Williams discovered what had been the largest and most violent race-based uprising to occur during World War II. It piqued her interest because it directly contradicted the commonly told stories of patriotism and unity of the era. It also reflected earlier iterations of issues with which the U.S. continues to grapple.

During two days in June 1943, 34 people were killed and 433 injured—the vast majority of them Black. The violence was brought to a close after 6,000 federal troops were sent to the city, leaving behind extensive property damage in the city's poorest neighborhood. Although it was deemed a race riot and is still referred to that way in many reference resources, Williams prefers "uprising," arguing that people were angry and frustrated and pushing back against a broken system. In fact, when the NAACP released a report about the cause of the events, they blamed a lack of decent housing, discriminatory employment practices, and police brutality.

“When I think of 1943,” writes Williams, “it is impossible not to see a long bloody thread of white violence, oppression, and police brutality drawn through the events of the past that connects our present moment with the rest of history. The issues present in the uprising of 1943 were the same ones present even before the Red Summer of 1919, the Tulsa Rebellion of 1921, the Watts Rebellion in 1965, the unrest in Los Angeles in 1992, Ferguson in 2015, and Minneapolis in 2020.”

Interviews provide intimacy and imagery

While the haunting resemblance between then and now pulled Williams into the history, it was her discovery of a cache of affidavits gathered by the NAACP that convinced her the topic was ripe for a graphic retelling. In the period during and following the violence, the organization set up an office to provide people with medical and legal aid and to collect statements about what they'd experienced. Their stories are rife with descriptive imagery and offer more intimate details about the lives of participants than some of the excellent academic histories of the event. (Williams especially relied on Layered Violence: The Detroit Rioters of 1943 by Dominic J. Capeci, Jr. and Martha Wilkerson, University of Mississippi Press, 2009.) The words gleaned from the affidavits became the heart of Williams’s project.

One group of affidavits on which Williams chose to focus were those of women: “Their voices have been nearly erased in the literature about the rebellion, although photos reveal that a number of women were present.” Williams wanted readers to really see these women and better understand the crucial roles they played in a complex historical moment at the intersection of gender, class, and race.

During the eleven-plus years she worked on the book, Williams made multiple trips to Detroit, visiting neighborhoods, archives, and museums. Via that fieldwork, she produced hundreds of sketches and took even more photographs. In order to “think in images,” she was determined to connect to the place. She revisited locales that have since vanished or been significantly altered, as well as studied old photographs to absorb the styles of the period. Dates and figures were important, as was intersectional analysis, but what sets her work apart from other books on the topic is Williams's attentiveness to visual detail. Her images capture period clothing and textiles, architecture and store signage, and product names and labels. Since the automobile industry plays a role in the story as the key economic engine of the city, which was then the fourth largest in the country, she also had to capture cars, though she sheepishly confesses, “I can’t draw cars.” And since she was unable to find a photographic record of many of the people in the book, many likenesses had to be “conjured.”

By shining her storyteller’s light on individuals, Williams wants to dispel the notion that the uprising was conducted by “aimless nihilists” without a clear purpose. “On the whole,” she says, “the uprising was a large event composed of smaller individual decisions, many of which caused harm, some of which showed deep compassion and bravery. [Those involved] were responding to years of simmering oppression and fear of scarcity. Whites were afraid of losing privileges and property, and Blacks were afraid of losing their lives.”

In the time that Williams worked on the book, not only did the world—both her own and the wider one—shift, but so did the materials available to her. “I work with aqueous media, and so I wanted the images to be on watercolor paper with ink and pen and some graphite," she explains. “By the time I finished the book, drawing on an iPad was actually a viable option. It made my work go so much faster and was more forgiving.” Eventually, she produced more than 200 9- by 12-inch drawings, each of which she scanned and then edited in Photoshop. “I rendered the final bits on my iPad. It took a decade for technology to evolve to the point that drawing with a stylus instead of a pen somewhat satisfied my tactical sensibilities as a painter.”

A haunting leads to a second project

While researching the causes of the uprising, one of which was rumors of violence against Black women, Williams encountered an allusion to Mary Turner. Following this clue, she read a seminal article by NAACP investigator (and its eventual president) Walter White about a spate of lynchings that occurred in 1918 in southern Georgia. Among the dozen people killed was Mary Turner, a mother of two children who was pregnant at the time of her brutal murder, which came on the heels of her demand for justice for her husband Hayes, who had been lynched.

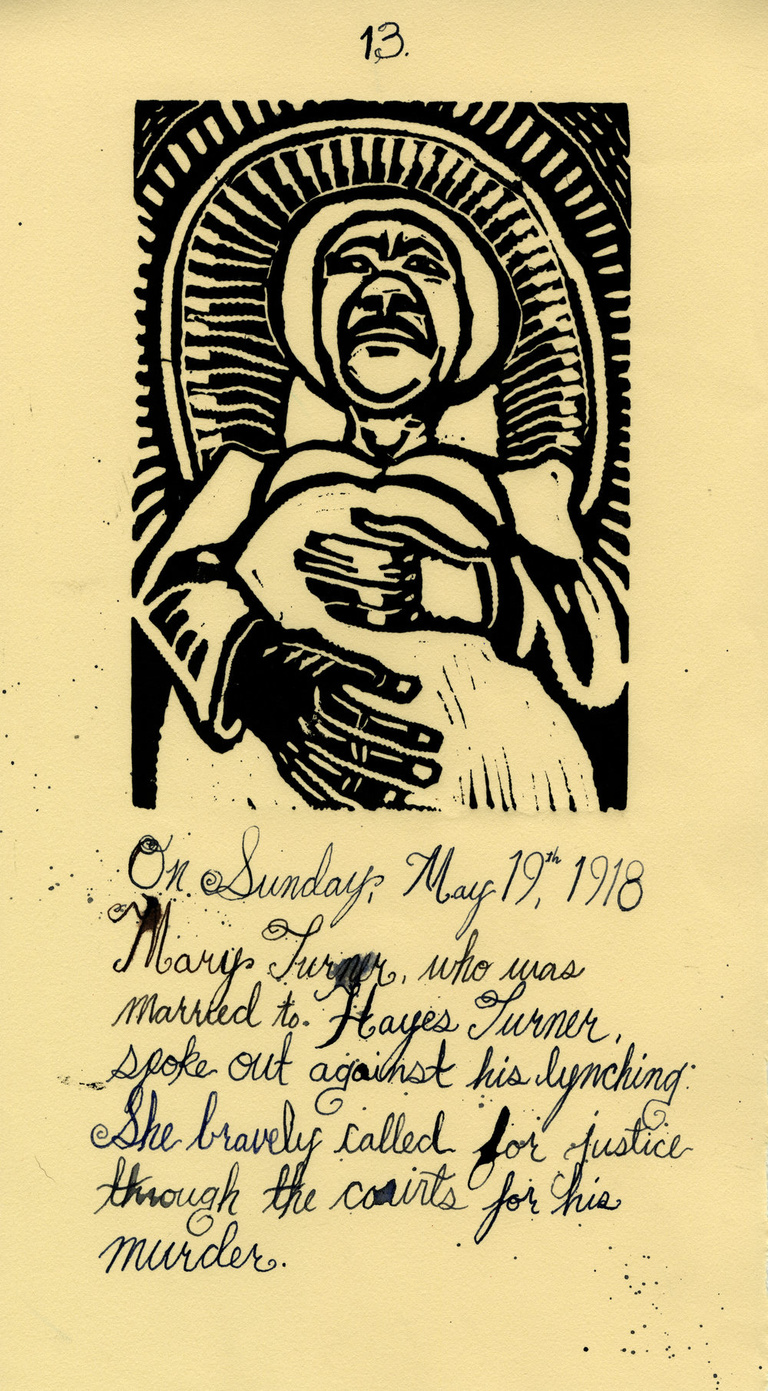

Williams, a native of North Carolina who spent many years living in Florida and driving through the section of Georgia where that earlier terror had occurred, says she was “haunted” by the images described in White’s report. She began a long process of creating linoleum block prints about the events. “I wanted to labor over each image,” she recalls. “I wanted them to be stark. Many of them were quite difficult to create in terms of the content. I wanted them to be raw and hard to see, to feel very close and personal, to put viewers in the shoes of witnessing.”

She’d initially thought the images might stand alone. Her inspirations were small, wordless novels featuring woodcuts by artists Franz Masereel and Helena Bochořáková-Dittrichová—work that scholars consider to be precursors to comics. Eventually, though, she decided that words were necessary to distinguish the individual victims and create a chronology of the crimes. Inventing an intentionally difficult-to-read script, she scribed a text that is neither exactly a history nor a story. The result is a harrowing testament to a dreadful event in U.S. history. The starkness of the style both demands to be viewed and conveys an intimacy that a written history cannot.

Confronting evil

In a review of the book, NPR’s Etelka Lehoczky writes, “Williams doesn't just deplore unspeakable evil or try to argue with it. She confronts it in its own realm—the realm of art. Lynching, after all, was no mere retribution. It was ritual.” And Deborah Whaley, a comics artist and UI faculty member in African American Studies and American Studies, says, “Rachel’s use of texture, color, and collage creates a layered visual aesthetic that conveys the atrocity of the murder of Mary and the unequal social relations that countless numbers of people of African descent experienced then and now. Women as victims of lynching are rarely a part of the discourse on public, vigilante, race-based violence. Thus, her graphic storytelling makes a larger intervention into American and African history.”

The book includes contributions from C. Tyrone Forehand, great-grandnephew of Mary and Hayes Turner, whose family has long campaigned for the deaths to be remembered; abolitionist activist and educator Mariame Kaba, reflecting on the violence visited on Black women’s bodies; and historian Julie Buckner Armstrong, who opens a window onto the broader scale of lynching’s terror in American history. All proceeds from the book will be given to the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, GA.

The two publications are Williams's first books, and they join an outpouring of her work that is incredibly rich and unique in its range of visual media. Since joining the UI faculty 1998, Williams has taught on the faculties of the College of Education, the School of Art and Art History, and the Department of Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies, while also serving as the UI’s Ombudsperson. She has won nearly every award for outstanding teaching and public service that the University gives. Friends and colleagues know her to be tireless in her commitment to the community. Trained as a doula, she has attended incarcerated women during childbirth, and she also volunteers at the Domestic Violence Intervention Program.

Not "just" a comic book

It is telling that in a faculty bio, Williams alludes to her “traditional research” as focused on women in prison. In fact, she has conducted research in more than seven carceral facilities and has led an educational practicum for students who worked with inmates at the Iowa Correctional Institution for Women in Mitchellville. Her scholarship often pushes beyond the boundaries of what has been conventionally recognized by higher education. In recent years, she co-directed the 2011 Obermann Humanities Symposium, “Comics, Culture, and Creativity"; her contributions focused on alternative and single-creator comics and graphic novels. Her graphic scholarship has been published by the Jane Addams Hull House Museum, the Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education, and the International Journal of Comic Art. She collaborated with Christopher-Rasheem McMillan (Dance and GWSS) on a dance and graphic performance about Mary Turner and worked with high school students and the National Czech and Slovak Museum to build an exhibit that featured a graphically rendered history of a group of Czech and Slovak fighters during World War I.

Williams, who worked on her book projects as an Obermann Fellow-in-Residence and has also served as co-director of the Obermann Graduate Institute on Engagement and the Academy, has long voiced the need for the academy to recognize and celebrate a wider range of work. Earlier in her career, she recalls having a conversation with an associate dean to “basically ask permission to make comics as my ‘research.’ The dean agreed it was fine as long as academic journals and presses were willing to publish them.”

Her colleague and comics historian Corey Creekmur (Cinematic Studies and GWSS) says that one phenomenon that fascinates him “is the scholarly graphic novel, fully annotated in the manner of solid academic research. If there’s still a tendency to dismiss such work as ‘just’ a comic book," Creekmur says, "this rigorous scholarly apparatus in many recent works at least gives pause to such easy dismissal. These are emphatically the works of a scholar-artist or, as I’m guessing Rachel would prefer, an artist-scholar.”

While Run Away If You Don’t Want to Be Killed was published by the University of North Carolina Press, Williams says of Elegy for Mary Turner, “That book is extremely unique and more like an artist’s book. People in academia did not know how to review it. I had to give up on getting an academic press to publish it.” In the end, she worked with Verso, which Harper’s refers to as “Anglo-America's preeminent radical press.” Verso has published authors such as Vivian Gornick and Rebecca Solnit.

Arriving at a seminal moment

Creekmur finds the simultaneous publication of the two books to be both a triumph and an indication of Williams’s deep talent. “My impression is that earlier, Rachel saw her relation to textual sources and historical events as an illustrator,” he says. “Language in such cases—often taken directly from archival sources—can seem primary, and images secondary, supplements to the written accounts, even when skillfully or beautifully done. [Elegy for Mary Turner] is an amazing, searing work, but to my mind, it’s not a comic—which is just fine. I think the dramatic difference between the style of these two works is a vivid demonstration of Rachel’s range and versatility, and a recognition that different stories demand different formal approaches.”

While Williams began these books years ago, their arrival seems almost prescient; they were published in Spring 2021, as the trial of Derek Chauvin got underway. Williams hopes that the books' appearance does much more than cause anger, repulsion, or guilt. “I hope this work pushes audiences to reflect on the ways that BIPOC members of our community continue to needlessly suffer, even today,” she says. “We must, as a nation, reflect on the ways that white supremacy is still shaping policy, law, and justice. Why are some white people silent, some emboldened? What can we change? Can we find the courage to speak out like Mary Turner? What are we willing to risk?”