Public Engagement 101

Publicly engaged work never occurs in a vacuum. That’s something Dr. Dellyssa Edinboro shares with her students at Bellevue College as she simultaneously encourages them to actively work to change systems of oppression. “When you move into spaces where you want to make change,” she says, “there are a lot of conversations that need to happen, some of which will have tension and conflict.”

Edinboro has firsthand experience of the kinds of twists and turns involved in a successful public project. In 2017, she was part of a small team of students that received a grant to work with the Historic Johnson County Poor Farm to produce a series of creative workshops about mental health. The students devised their project as part of the Obermann Graduate Institute on Engagement and the Academy with encouragement from the County staff member who managed the space. The first twist occurred when a key team member, who was an MFA student in the Dance Department, left the project. Without his expertise, it no longer made sense for the group to focus on movement as their primary form of creative expression; instead, they switched to creative writing. To get sign-off on using the Poor Farm space, they were told to present at a Johnson County Board of Supervisors’ meeting; it was a formality, their liaison had assured them. After waiting through the meeting, however, Edinboro and her team partner introduced themselves and the project only to be met with a baffled reply from the elected officials who had never heard of the project and notified the students that their contact was no longer working there.

In retrospect, the experience was Public Engagement 101 training in action. It provided Edinboro with a firsthand lesson that could be titled "Always Expect the Unexpected." And it was a reminder of how the parties involved in a collaboration often morph. The experience served Edinboro well when, three years later, she became a Humanities for the Public Good intern for the Center for Afrofuturist Studies (CAS), a non-profit that resides within Public Space One. At the time, Edinboro was a PhD candidate in the UI College of Education in the midst of writing her dissertation and looking for jobs. The internship sounded like a good way to continue her interest in publicly engaged scholarship. What she hadn’t foreseen, however, was doing a supposedly public-facing job entirely from her living room.

Internship Responded to the Moment

The Center for Afrofuturist Studies funds artist residencies, produces exhibitions and workshops, and maintains a growing public reading room and archive. Central to its mission is "to rethink and challenge what an arts practice that revolves around Black futurity looks like," which, it says, is "only possible when arts organizations commit to fully supporting the work being done by Black artists." Given its focus, it was a given that the death of George Floyd and the protests of that summer radically shifted the focus of Edinboro’s internship.

In a blog post from July 2020, Edinboro wrote, “I am grateful to CAS because my responsibilities did not exist in a vacuum but in the moment I am living in.” She went on to describe helping to draft a statement “advocating for radical and lasting racial change” and affirming the importance of Black artists to use their “collective imaginations to envision a future where Black people can construct lives centered around joy, autonomy, and innovation.”

Those words would be at the center of Edinboro’s next chapter with CAS.

“I wasn’t ready for it to be done,” she says of her internship and her decision to become a permanent member of the CAS team as its education coordinator, working directly with CAS’ visionary founder and curator An Duplan. In August 2020, CAS and Public Space One were approached to help oversee a mural that the City of Iowa City envisioned as a response to the protests of the summer, and which was funded via a 17-point resolution unanimously passed by the City Council and inspired by the demands of the Iowa City Freedom Riders. Edinboro was involved in meetings about the potential focus of the piece, prospective artists, timelines, costs, community outreach, and more. Although significantly larger than Edinboro’s Poor Farm project, the mural involved similarly complex issues of competing visions and an evolving team.

Language Matters

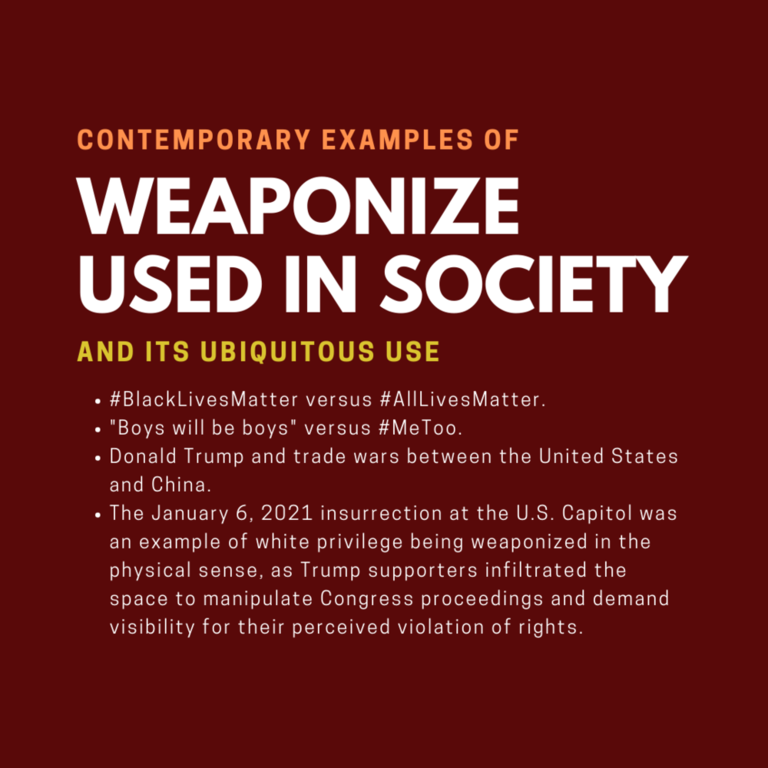

At the core of the team were the selected artists, Antoine Williams and Donté Hayes, both of whom had worked with CAS previously. When they provided their design for what is now known as The Oracles of Iowa City, the City’s Public Arts Committee hesitated. “They were fine with the Joy mural," recalls Edinboro. "The one that led to conversation was Weaponize." She said that Williams spoke about what the words meant to him and stood by the design as it was. In response, the Committee asked for public input in the form of research, conversation, and a survey.

Edinboro was central to this step of the mural process. She helped to edit the survey, which asked about the perceived audience of the murals and the purpose of public art, among other things. She also performed research into the primary terms of both murals.

Tracing the history of the problematic word “weaponize,” she paraphrased an article by scholar Greggor Mattson, “Weaponization: Ubiquity and Metaphorical Meaningfulness” (Metaphor and Symbol, Vol. 35, 2020): “In contemporary usage, weaponize means the recent and illegitimate transformation of something into a weapon of thought for urgent and motivational public discourse and a heightened awareness about social issues.” Distilled into colorful slides and print material, the information was presented to the Public Arts Committee, which approved funding for the project in Winter 2020. (Both the survey results and Edinboro’s research slides can be found at https://www.publicspaceone.com/oracles-of-iowa-city-feature).

Midway through the process, Edinboro wrote a powerful op-ed in the Iowa City Press-Citizen. She quoted Williams, who said, “the mural in itself is not enough,” and she argued that the mural “reflects Iowa City’s commitment to confront its anti-Black practices, especially after this year’s local and national protests.” She provided examples of the concrete ways that the mural’s production contributed to training and payment of Black artists and fostered public conversations.

Connecting to Her Dissertation

Edinboro says that throughout the process of gaining approval for the Oracles project, she often thought of the women who were at the heart of her dissertation—four Black women who had each gone abroad in the first half of the twentieth century to pursue diverse educational opportunities. One of them, artist Loïs Mailou Jones, received a General Education Board fellowship to study in Paris in the 1930s. While attending a Parisian art school, she was praised for her impressionistic art style, but, says Edinboro, “when she explored African themes in paintings such as Les Fetiches (1938), she got pushback.” The pushback that the murals received, and the way that an all-white committee was serving as a gatekeeper to Black artists, felt to her like an echo across multiple generations.

From her new home in Washington state, where she is assistant professor of Cultural and Ethnic Studies at Bellevue College, Edinboro is still working with CAS. She jokes that the staff got quite good at working via Zoom during the pandemic, so their geographical distance isn’t as much of an issue as it might seem. Via a Humanities Project Grant from the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs that specifically calls for a humanistic approach to public programming, the Oracles team is imagining new ways to use the murals as intended and as laid out on the Public Space One website: "The point of the Oracles project is to have these difficult and oftentimes uncomfortable conversations that acknowledge Black people’s lived experiences and humanity, creating a space where their voice can be centered rather than unheard or ignored in favor of white comfortability and tokenization.”

On March 3, 2022, Edinboro will be a panelist in an Obermann Conversation that uses the Oracles project to consider the role of public art while also providing a behind-the-curtain look into the many decisions and conversations necessary to bring works of this scale to fruition. She'll be joined by two other members of the Oracles team, PS1 board member and local mural champion Thomas Agran and lead painter Jill Wells. Tracy Molloy, a New York City-based public artist, will provide context from projects in other parts of the country. The event is free and open to the public; Zoom registration is required.