Photo above: “Jitterbugging at the Railhead: Spontaneous gaiety breaks out among troops at Railhead, Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia, as they prepare to embark for overseas. Jitterbug couple shown here, dancing to tunes by Camp Patrick Henry Jazz Orchestra, are Pfc. Walter Pogorzelski and Betty Brewer, American Theatre Wing actress.” National Archives.

“When we think about performance during World War Two, we think about USO shows and famous American performers like Bob Hope and Bette Davis,” says Rebekah Kowal, Spring 2022 Obermann Fellow-in-Residence. On the face of it, these performers were sent to overseas U.S. military camps to uplift soldiers’ spirits by providing a sense of home and “Americanness.” But there were many other forms of movement and performance that served other (rather overt) purposes, from displaying Western cultural dominance and exerting control over subjected people’s bodies to reintegrating the detained, creating a pathway to U.S. citizenship, and serving as a normalcy touchstone for the dancers.

Kowal (Dance, CLAS) is deep in research for a new book tentatively titled War Theatre: Dancing American Citizenship and Empire during World War II. After writing about the contribution of American modern dance to aesthetic and social change in the 1950s (How to Do Things with Dance: Performing Change in Postwar America [Wesleyan UP, 2010]) and about globalism and the performance of international dance in the U.S. after WWII (Dancing the World Smaller: Staging Globalism in Mid-Century America [Oxford, 2019]), she figured her next project would move away from the WWII era. But one sleepless night—“one of those bizarre moments during COVID,” she recalls—she pulled up the National Archives’ online catalog and started typing keywords. To her surprise, “over a hundred images popped up under the combined search terms ‘war’ and ‘dance.’” Images she’d never seen before and that, she noticed, fell into a few broad categories: photos of American soldiers spontaneously breaking into dance (see “Jitterbugging at the Railhead,” above); photos of formal dances at officers’ clubs around the world (above, right); photos of locals performing traditional dances at American military camps abroad while U.S. service members watch (above, left); and photos of Japanese Americans in internment camps participating in both formal and casual dances (below). Some of these photos struck Kowal as particularly strange: “It was almost as though the dancers were performing for the photographer.” Were certain performance events staged for the sole purpose of being photographed? she wondered.

Context Lost

The more photos she found, the more questions she had: Who staged these various performances, and what, besides entertainment, did they provide their participants and their audiences? When they were photographed, who photographed them—a bystander? a professional? a service member?—and why? Were the photos ever disseminated during the war? After the war? If so, to whom, in which venues, and/or to what end(s)? Kowal began searching for answers, but the task was remarkably difficult, as many of the photos had been severed from their context. Often the National Archives’ listing for each photograph includes only a date and a short caption that may (or may not) mention the setting, and all of which have been processed through military/intelligence censorship via the Office of War Information.

Because it’s nearly impossible to discern the specific contexts of the photos, Kowal has been using supplemental primary and secondary source materials to piece together the larger context of dance in internment camps and at military bases. This includes ethnographic studies of Japanese-American detention camp internees, which describe the inmates’ daily lives; or newsletters and high school yearbooks published at the camps, which include announcements and reports of various dance and community events such as parades and performances. But first-hand accounts of the events are the most useful of all—and luckily, Kowal has discovered a handful of well-known dancers who were involved in wartime performances and whose stories, she says, “we can actually track through World War Two.” Through these dancers’ letters, journals, and other writings, she’s learning about the various roles dance—and, more broadly, performance practices—played during the war.

Three Wartime Dancers

José Limón, a preeminent modern dancer and choreographer, was conscripted into the U.S. Army Special Services in 1942, where he was able to continue his dance practice, choreographing and performing in shows to entertain his fellow service members (see photo, right). Limón’s thoughts and feelings throughout his military service until 1944 are well documented in correspondence between him and his wife, Pauline Lawrence Limón. In a letter to his wife dated July 1943, early in his basic training, he wrote:

“I am always so happy to hear from you and you must understand that I do not write as often as I would like because this period is utterly fantastic. You can’t know about it. If you do not yourself experience it—we live with the guns and gas masks and cartridge belts and get up hours before day and march and go on bivouac and obstacle courses and gas chambers etc. and retire late at night and have gas alarms etc. etc.—we have gone beyond fatigue—into stupor—I have adopted an attitude of detachment and calm—as the only means of emerging with any degree of sanity—there will be 4 more weeks of this—and then what? I don’t know—I do know however more than ever that I wouldn’t wish this on to my very worst enemy, whoever that may be. All of your news sounds as from another planet—another age—another species of beings—it’s hard to believe.”

Pauline Lawrence Limón papers collection, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

The couple’s letters reveal strains in their relationship as well as their mutual concerns about the toll of military service on José’s career as a dancer and choreographer. What’s especially notable in this case, says Kowal, is that Limón was a U.S. resident alien at the time; his parents were Mexican immigrants. WWII military service was a path to American citizenship for many Mexican Americans—and Limón’s work at Fort Lee—his military service, essentially—helped earn him citizenship in 1947.

Walter Terry was the chief dance critic for the New York Herald Tribune. Drafted in 1942 and sent to North Africa, he spent his free time teaching American modern dance and dance history to Egyptian students at the American Mission College for Girls, lectured on American dance to the Allied Forces in Cairo, and starred as the principal dancer in a production of Rosemarie at the Cairo Opera House. Later, he’d describe dance as an “intercultural bridge.”

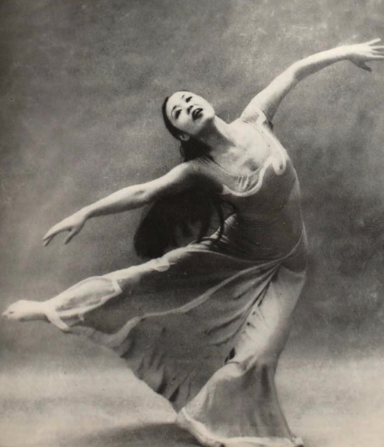

Yuriko Anemiya Kikuchi, a Japanese American dance artist known today as one of Martha Graham’s leading dancers, was detained for 18 months at two different internment camps after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. At both camps, she earned money by teaching dance to young Japanese American girls and their mothers. “What’s remarkable,” says Kowal, “is that she was elevated—and paid—as a professional, the same way the doctors and dentists at the detention center were paid for their services.” Kikuchi wrote later that, as an American by birth, she felt “othered” for the first time when she was forced into the camp. “Her ability to continue the practice of dance—through teaching—helped to connect her with her former, familiar identity,” says Kowal, as it grounded her both physically and mentally.

In a Dance Magazine interview, Kikuchi says of her Gila River Camp dance classes, “I just didn’t want to see the children go nuts. Besides, I didn’t want to go nuts, too.” She goes on to describe dance as “survival,” saying, “It saved my life.” Indeed, in 1943 she acquired an American sponsor who respected her talent, and she was allowed to leave the camp before most everyone else. Almost immediately, she connected with Martha Graham, who told her, “If you’re good, you will be accepted.” And, of course, she was. Dance, for Kikuchi, was a direct route to reintegration and acceptance.

Kowal is currently drafting the chapter on Kikuchi and looks forward to visiting the UCLA’s Special Collections, where many of the dancer’s letters are stored. She hopes to learn more about Kikuchi’s frame of mind while incarcerated and the ways in which her regular dance practice and role as an instructor may have supported Kikuchi’s resilience and helped her to process physical and emotional trauma. Choreographic works that Kikuchi created in the mid-1960s, which incorporate self-performed solos, suggest as much in the ways they embody conditions of isolation, ostracization, and self-soothing.

Context Flipped

Attempting to replicate the economic, social, and cultural structures of civil society, the U.S. War Relocation Authority established systems of labor and leisure at the Japanese internment camps that mirrored life outside of the camps. These included work activities such as farming and manufacturing for skilled and unskilled laborers, on the one hand, and professional work for those in medical, educational, and artistic fields, on the other. Authorities promoted the “well-rounded recreational program,” including activities such as sports, arts and crafting, performing arts, movies, playgrounds, and clubs for children, as “providing recreation for ninety percent of the people” (Tulare News Review).

Kowal doesn’t yet know to what extent photographs of these camp activities were disseminated during the war, but she has found propaganda films produced at the same time that depict similar events and were intended for consumption by the American public. In one such film, the narrator justifies the treatment of incarcerees, saying, “We are protecting ourselves without violating the principles of Christian decency. We won’t change this fundamental decency no matter what our enemies do.”

As Kowal argues, the U.S. government’s justification for its treatment of detainees as aligning with senses of “Christian decency” or “fundamental decency” was based on its “allowing” or “permitting” space and time for recreative activities outside of this (forced) labor. In this sense, documentation of detainees’ engagement in dance and leisure practices were likely used as evidence of the government’s humanity even as it engaged in a campaign to deny citizens their basic human rights.

The War Relocation Authority hired well-known photographer Dorothea Lange to document the wartime internment of Japanese Americans; she, however, made photos critical of the internment (perhaps humanizing the detainees "too much"), and the military immediately censored them. (See Lange's photos.)

Interestingly, says Kowal, as the war progressed, the U.S. realized it would have to reintegrate the Japanese American detainees into society, so government officials began circulating photos of “familiar American activities” they’d arranged for camp incarcerees: Christian church services, Boy and Girl Scout meetings, high school barn dances, Thanksgiving harvest festivals, parades, plays, wrestling tournaments, baseball games, football games. (How widely these were circulated, and to what extent they influenced the detainees' reintegration, we don't know.)

So far, Kowal has visited the New York Library for the Performing Arts to study Jose Limón’s, Walter Terry’s, and Yuriko Kikuchi’s papers, and she anticipates visiting the Library of Congress to search its archive of WWII American soldiers’ letters home. She also hopes to interview Japanese American choreographer June Watanabe, who was detained from age three to six, and who has created several dances based on her experiences at the internment center. “I’m really excited about her," Kowal says—"meeting her, talking to her, analyzing her dances.”

Kowal's book will likely be published by Oxford University Press.