How would you feel if, in the middle of a conversation, you couldn’t come up with the word for water, shirt, or table—or your own name? If suddenly it was a struggle to comment on a movie or tell a simple story?

You’d likely feel confused, embarrassed, frustrated, scared.

According to the National Aphasia Association, over two million Americans suffer from aphasia—the inability to speak, write, and/or understand language as a result of brain damage, usually stroke—making it more common than muscular dystrophy, Parkinson’s, cerebral palsy, and multiple sclerosis. Severity and symptoms vary but can include speaking haltingly; struggling to construct a sentence; using wrong but related words; speaking and/or writing in fragments or nonsense words; and having trouble understanding text or conversation. Aphasia can be devastating to a person’s social connections, emotional well-being, and overall quality of life.

“We’re used to thinking of communication as transactional,” says Jean Gordon, Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Sciences & Disorders and a Fall 2019 Obermann Fellow-in-Residence, “but even more importantly, it’s interactional. It’s our way of connecting with other humans and demonstrating who we are.”

People without aphasia tend to have difficulty connecting to those with the condition, she notes, even when the person is able to communicate nonverbally. As a result, people with aphasia often become withdrawn, lonely, and isolated. In fact, thirty percent of people with aphasia in a 2006 study reported having no remaining friends after their stroke—and, according to the National Aphasia Association, aphasia has a greater negative impact on a quality of life than either cancer or Alzheimer’s Disease.

A Diagnostic Dilemma

That’s why it’s crucial that people suffering from aphasia get accurately diagnosed and treated. However, there’s a longstanding problem of diagnosis—one that Gordon is taking important steps to address.

Currently, to determine whether someone has aphasia—and, if so, which type—a speech-language therapist asks the patient to complete a series of verbal tasks. These can include describing a picture, engaging in conversation, telling a story, answering questions about something read or heard, repeating words and sentences, answering questions about common subjects, reading, and writing. The clinician then rates the patient’s performance and applies a diagnostic label.

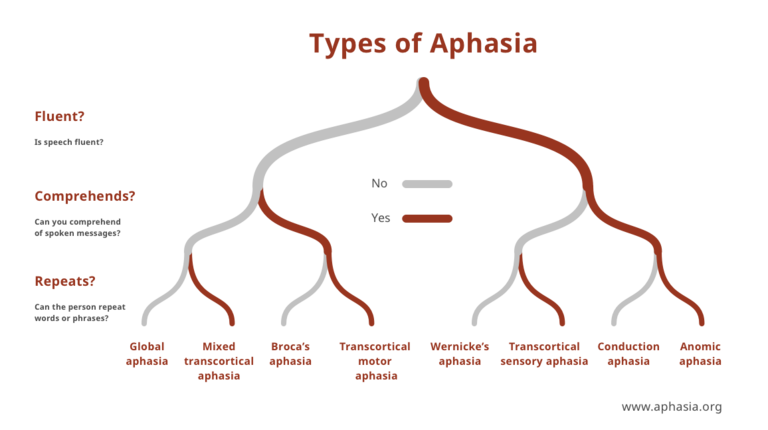

There are many types of aphasia, depending on which regions of the brain are damaged, but the disorder is generally divided into two broad classes: fluent and non-fluent. People with non-fluent aphasias struggle to put sentences together and speak haltingly, in fragments, whereas those with fluent aphasias speak in relatively complete—but often incoherent—sentences.

Gordon, who directs the UI’s Language in Aging & Aphasia Laboratory, says the current measures of fluency view these two types as distinct—but in reality, there’s a great deal of overlap between them. For example, some people classified as non-fluent can retrieve lots of nouns but few verbs or connecting words; they might say, “Store. Need milk. Tomorrow.” Some fluent patients might have trouble with nouns, saying, “That guy in that movie with the thing…”

The unreliability of fluency classifications has been a well-known problem since at least the 1960s, related to the many factors that can disrupt fluency—problems retrieving words, difficulty forming grammatical sentences, or difficulty articulating them smoothly. But Gordon says most clinicians have resigned themselves to the difficulty, figuring their own ways around it—for instance, by choosing a measure that correlates well with fluency/non-fluency (such as speech rate or length of utterance), even though no single measure can capture all of the reasons why someone might not be fluent.

A Better Way

Gordon is addressing this unreliability by developing a new method to assess fluency, tentatively called the Iowa Fluency Test. A clinician using the aptly nicknamed “IF Test” would ask a person with aphasia to perform a number of verbal tasks, then take several different measurements—some objective and some subjective—that collectively pinpoint the patient’s most significant language difficulties. Knowledge of those specific deficits, then—rather than a label referring to a general category of aphasia—would guide any subsequent therapy, hopefully making it more effective.

The tool itself would take the form of a decision tree. In Gordon’s words, “If you see this, then either it’s because of this, this, or this. Each step of the decision tree will interrogate each of the possibilities.”

Gordon admits feeling resigned to the diagnostic problem herself until 2016, when students in one of her classes vociferously lamented the unreliability of the testing battery. “Finally, I thought, ‘Yeah, they’re right!” she says. “There’s got to be a better way.’” When she asked her students if they wanted to help her develop a tool that would give clinicians a more nuanced view of their patients’ aphasias, one student—Sharice Clough—volunteered. Gordon and Clough went on to write an American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation grant application for their project, “Fluency Forward: Developing a more reliable and clinically useful assessment of fluency in aphasia,” which the ASLHF funded in 2017. Since then, they have co-authored two papers arising from the project that are currently under review.

The IF Test is currently in the conceptual stage, as Gordon is in the process of collecting responses from speech-language clinicians around the country about their methods of measuring fluency. In late November, she’ll present her research and a preliminary version of the tool at the ASHA Convention in Florida. And by 2021, she hopes to have a nearly finalized version of the IF Test that she can take to clinics around the U.S., giving instructional workshops, observing clinicians use the test, and collecting feedback. Eventually, she’ll make the tool freely available online for any clinic to use.

A Misunderstood Disorder

Though one-third of all strokes result in aphasia, only 15 percent of Americans have ever heard the term “aphasia,” according to the NAA’s 2016 Aphasia Awareness Survey.

The word “aphasia” itself—from the Greek “no language”—is somewhat of a misnomer, as people with aphasia typically retain some use of language functions. But again, severity and competencies vary, depending on which regions of the brain are affected. It’s this ambiguity, as well as the lack of public education on aphasia, that makes this disorder so difficult to understand.

“Public awareness is a huge problem in our particular corner of the world, primarily because people with aphasia aren’t good advocates for themselves,” says Gordon. This is because they often have difficulty telling their own stories—and may never be able to do so effectively, as complete recovery of language ability is often impossible.

There was, she notes, an increase in aphasia research and public awareness following World Wars I and II, when soldiers who’d suffered gunshot wounds to the head returned home with language difficulties. And, in the past few years, the condition has made occasional news as former congresswoman Gabby Giffords and Game of Thrones actress Emilia Clarke struggle toward recovery. But an ounce of publicity is nowhere near enough.

As with any disorder, an increase in public awareness is connected with increased efforts to improve and extend services to people with the condition, to increase research support for those who study it, and to improve the social inclusion of victims. Social inclusion is especially crucial for people with aphasia, as those with no knowledge of the disorder often perceive halting and disordered speech as a sign of intellectual impairment or even drunkenness—and treat the speaker accordingly.

Gordon encourages everyone to learn about aphasia, so that they can facilitate the ability of people with aphasia to navigate the world. She recommends the following resources as starting points:

Websites:

Videos (the first two are freely available online):

- After Words

- Speechless

- Aphasia: Hope Is a Four Letter Word [link removed]