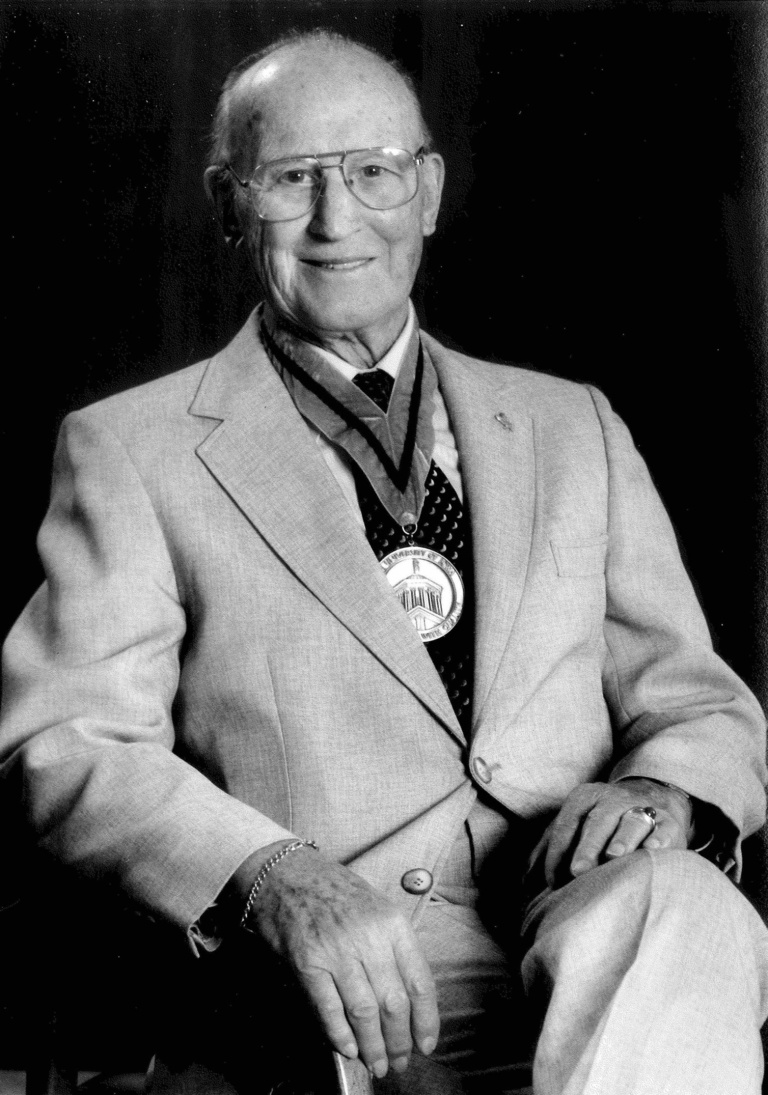

Esco Obermann embodied interdisciplinarity. That's him in the photo to the right, upside down on his parents' windmill in Yarmouth, Iowa. (Look closely—the soles of his shoes are aligned with the motor.)

Esco, one of nine siblings, grew up doing acrobatics on his family's farm in southeastern Iowa—backbends on bulls, rope stunts in haylofts, L-sits on windmills—as if driven to seek new perspectives. Little did he know that this proclivity would lead him to renown not as a gymnast but as a champion of interdisciplinary research and as an incredibly generous donor to the University of Iowa.

A Tour of Duty...and the Midwest

Esco majored in political science at the University of Iowa, where he also competed with the gymnastics team and sang with the glee club. His passion for singing briefly led him to seek a career as a self-styled "pseudo-Irish tenor" in Chicago, but his interest in social service won out; he returned to the UI to earn an M.Ed. (1931) and a PhD in clinical psychology and speech pathology (1938). Along the way, he married his dear friend Avalon Law, a UI College of Education alumna from Washington, Iowa.

After six years in the U.S. Air Force during WWII, Esco began a counseling career in Minnesota high schools and in the U.S. Veterans Administration, where he helped to craft the widely acclaimed 1944 GI Bill. The legislation provided, in addition to financial and medical benefits, unprecedented educational support for veterans.

It was during his tenure as GI Bill Administrator for the Upper Midwest that Esco realized the necessity of interdisciplinary approaches to rehabilitation counseling. “Almost every problem [I encountered] presented multiple dimensions,” he told the UI Foundation (now the University of Iowa Center for Advancement) in 1992. “The individual veteran had to deal with social, medical, legal, and psychological aspects of his or her disabilities and adjustment problems.” Which meant, of course, that in order to help veterans adjust to civilian life, their counselors had to cross disciplinary boundaries, too. The trouble was, most counselors were trained in only one or two fields.

Envisioning a "Think Pot"

Naturally, when Esco joined the UI faculty in 1966 as an associate professor of rehabilitation counseling, he began advocating for the establishment of a center where practicing and trainee psychologists could be educated in a broad array of disciplines by experts across campus. He would later widen this focus to include research in every discipline, lamenting what he called in his correspondence with UI colleagues the "tendency towards fragmentation of knowledge."

"He was a very forward thinker," remembers Colleen Byrnes, who, as a UI nursing student in the late 1990s, was placed with Esco as an aide. "He always told me that his goal was to create a ginormous ‘think pot’ so all of the experts could come to the table, put their egos aside, introduce their ideas, support one another, and help to grow." Though the whereabouts of Avalon's letters and records are unknown, she likely shared her husband's vision; Esco consistently uses "we" rather than "I" in his correspondence with the university, and according to all accounts, the two were inseparable.

While the history of academia is punctuated with calls for interdisciplinarity, these often focused on teaching. Advocates became vociferous in the 1960s and '70s, as they feared that overspecialization was failing to equip students to address pressing social issues. Like higher-ed reformer Rustum Roy, who famously wrote, "the real problems of society do not come in discipline-shaped blocks" ("Interdisciplinary Science on Campus: The Elusive Dream," 1979), Esco was an early supporter of holistic, collaborative approaches to problem-solving, particularly in the helping professions. In a 1962 editorial titled "Habilitation Services for Children," he writes, “competitive, go-it-alone approaches will never get the job done"—and in a 1968 article in the Journal of Rehabilitation, he asserts that a client-centered approach to rehabilitation counseling is necessarily a collaborative one, requiring social workers and counselors to "work together with maximum integration and coordination, to meet the needs of the client rather than their own needs or the needs of their professions or agencies."

Establishing an experimental new unit at a state institution was a lofty goal, to be sure—but one that Esco the windmill acrobat, Esco the tenor, Esco the author of the landmark History of Vocational Rehabilitation in America, was uniquely suited to achieve.

Patience, Agility, Focus

The same qualities that helped him balance upside-down on a draft horse would eventually help Esco clear the bureaucratic hurdles inherent to establishing what would eventually become the Obermann Center for Advanced Studies. Beginning in the 1960s and through the '70s, he exchanged hundreds of hand- and typewritten letters with the UI Foundation, the UI President's Office, and other UI administrators about this provisional center, at the time called "University House" and directed by Jay Semel.

Throughout his correspondence, Esco is eloquent, gracious, humble, and eternally patient. "I hope that my continued pressing for commitment to University House does not generate irritation among the University's administrators," he writes in one letter. "I try to believe that my persistent expression of interest in University House and in an interdisciplinary mission for it does not reflect an unacceptable level of self-interest. If it does, I still do not feel like apologizing for it."

Colleen recalls a quirky anecdote that pointedly illustrates Esco's wit and ingenuity. When driving from Iowa City to his retirement property in Minnesota, she said, Esco would put a Hawkeyes baseball cap in the back window of his car. Then, when he reached the Minnesota border, he’d swap it for a University of Minnesota Gophers cap. "He thought that would be better for the state patrolman in case he got pulled over for speeding," she laughs.

University House was established in 1978 with the Obermanns' enthusiasm and nurture (along with that of many others). As long-time Obermann Director Jay Semel recalls, it grew "from an outpost with a handful of exiled professors" into "an important catalyst for interdisciplinary research," and a unit that has nurtured well over 1,300 scholars at the University of Iowa and elsewhere through its programming.

A Fourfold Return

Colleen received an inside glimpse of Esco’s lively, generous spirit. By the time she met Esco, Avalon had passed away, and Esco was undergoing cancer treatment. Colleen would occasionally help him with physical therapy exercises, but mostly she served as his chauffeur and friend. “I’d drive him around in his big Lincoln, wherever he wanted to go," she recalls. "It was a great gig. I remember thinking, for an older fella, he sure is pretty hip! How can I have so much in common with this man who's 70 years older than me? He was very young-spirited and sharp as a tack.” At the time, she says, he was still taking singing lessons and readily serenaded visitors with a joyful rendition of "Danny Boy."

In 1993, the UI Center for Advanced Studies was rechristened the Obermann Center for Advanced Studies in recognition of Esco and Avalon's enduring support. The two had donated substantial funding, including part of their estate, to expand the unit's interdisciplinary programming. "We think giving support to this center represents the most enduring and worthwhile thing we can do to make something contributory out of our lives,” Esco said at the time. Colleen remembers that Esco was very proud of this gift. “He grew up very frugally and was frugal throughout his life," she recalls, "and he said that when he was deciding what he and Avalon would do with their wealth, he never dreamed as a child on the farm that he would grow up and be able to donate this much money."

He rarely discussed his career or rehabilitation counseling when she knew him, says Colleen. "At that point in his life, he was entirely focused on philanthropy." But, she adds, "he did talk about Avalon every day. He loved her and missed her." Colleen frequently accompanied Esco to the Obermann Center’s first location at the Oakdale campus, where he had an office. She helped him sort through his vast personal library there, most of which he donated to the UI Libraries. "It was really, really hard for him to give up his books," she remembers, "but he always taught me that whenever you donate something, it will come back to you fourfold.” The two of them continued their friendship long after Colleen graduated and moved away; she even brought her infant daughter Alexandra (now a UI junior) to Iowa City to meet him shortly before he passed away.

Esco died in 1999 at age 94. In a lovely published by the Iowa City Press-Citizen, David Dierks, a longtime friend of Esco's and vice president for principal gifts with the UI Center for Advancement, recalled, "Everybody was fascinating and interesting to him. No matter how bad your day was going, if you talked to Esco, you would always feel better."

Sticking the Landing

Just as UI Men's Gymnastics continues to honor Esco with the annual C.E. Obermann Award, presented to an "outstanding senior for a career of excellence in scholarship, sportsmanship, and gymnastics performance," we at the Obermann Center try to keep Esco's interdisciplinary spirit alive in everything we do, from our Fellows-in-Residence biweekly seminars to our new Andrew W. Mellon Foundation–funded "Humanities for the Public Good" programming. Given Esco's passion for disability rights, we hope he'd be especially supportive of our 2019 Obermann Humanities Symposium, "Misfitting: Disability Broadly Considered," which will bring scientists, humanities scholars, and artists together to discuss the relevance and importance of disability to their respective fields.

As for gymnastics, Esco remained a dedicated athlete all his life. Anyone who knew him likely witnessed him do a handstand on a coffee table or at the annual UI Gymnastics Banquet—even into his 80s. (How we wish we had a photo of that!) Ben Ketelson, Assistant Coach of UI Men's Gymnastics, notes that Esco remains an enduring presence in the traditions of the team—chiefly in the form of a large bell that he donated many years ago and that the team carries in the homecoming parade each year. "And just this year," says Ketelson, "we started including it in our meets. Whenever somebody sticks a landing, they go over and ring the bell."

It's only fitting to end with Esco's own voice. His President's Message in the March 1963 issue of the Journal of Rehabilitation ends with this gentle, visionary call to action:

And so I invite you to a new level of participation in and new enthusiasm for the kind of citizenship that can save our culture and our world. Perhaps it will come to pass that through our love and unselfishness and understanding and intelligence and morality, we shall be equal to the requirements of our times; we shall solve the problems of how to preserve human values in great masses of human beings; we shall be able to understand and control our technology; we shall learn to love our neighbors as ourselves; we shall make peace, not war—and you and I and our fellow men will survive to reach the destiny intended for the human race.

Many thanks to Colleen Byrnes, a nurse practitioner in family medicine and ER at the Mitchell County Regional Health Center in Osage, Iowa.

Rustum Roy's article, "Interdisciplinary Science on Campus: The Elusive Dream," first appeared in Interdisciplinarity and Higher Education, ed. Joseph J. Kockelmans (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1979).

For additional photos, please visit the archived version of our website.