How often do you spend time with people significantly older than you? Not very often, if you’re like most Americans. “We live in an age-segregated society,” notes Mercedes Bern-Klug, professor, mentor, researcher, and practitioner at the UI School of Social Work. “Young people hang out with young people. Teenagers hang out with teenagers. There are few opportunities for the generations to mix, outside of places of worship.” Plus, she says, contemporary American society tends to view life after 30 as, well…boring. As a result, many young people miss out on intergenerational interaction and its many benefits: reduced loneliness, improved mental and physical health—and, particular to adolescents, identity formation, skill development, and academic improvement. They also tend to miss out on career opportunities working with the ever-growing senior demographic. (Americans 65 and older are projected to make up 23% of the U.S. population within the next 30 years.)

“Almost every health field is struggling to recruit enough students who want to work with older adults,” says Bern-Klug. To partly address this problem, the School of Social Work has created two general education courses aimed at freshmen—“Aging Matters: Intro to Gerontology” and “Mental Health Across the Lifespan”—with the hope of reaching more students.

More than piano lessons

When I ask Mercedes why she wanted to study the aging process as an undergraduate in the 1980s, she grins: “I know exactly who got me interested in older adults. It was Lillian Mousseau White in Sioux City, Iowa.” White was her grandmother's best friend and an accomplished violinist, pianist, and composer. “I didn’t meet her until she was in her eighties,” says Bern-Klug. “My sisters and I would go to her home for piano lessons on Saturday afternoons, and she’d tell us stories about our grandmother, who died before we were born. Those insights were so precious to us.” When White moved to a nursing home, Bern-Klug observed the transition with interest. “Learning about all these systems that she was interacting with while I was in junior high and high school opened my eyes to things that I never would’ve known about otherwise.”

Bern-Klug became one of the first undergraduates at the University of Iowa to earn a Certificate in Aging Studies. (That program, founded in 1980, is one of the longest-lived gerontology programs in the U.S. Undergraduates can earn a minor in Aging and Longevity Studies, and graduate students can earn the certificate.) Bern-Klug’s first exposure to research came as part of an undergraduate work-study position helping to pilot-test a survey; her job was to administer the survey to older adults. “I didn’t see myself as a researcher at all,” she recalls, “but when I told my advisor [Lorraine Dorfman] about the experience, she looked at me and said, ‘You know, you’re a researcher. You think like a researcher. You should seriously consider research.’ She was right!”

She went on to earn a Master of Social Work degree at the UI and later, an MA in Applied Demography at Georgetown University and a PhD in Social Welfare at the University of Kansas. Since 2004, she’s been on the Social Work faculty at the University of Iowa, coordinating the Aging and Longevities Studies certificate program and directing the School of Social Work during the trying years of COVID (2020–2023). Wherever she has worked or studied (she’s a social worker by training as well as at heart), Bern-Klug has surveyed her environment and its people, identified unmet needs, and taken steps to improve the lives of older adults and the systems that support them. In D.C., she led an Alzheimer’s support group for spouses and adult children of persons impacted by dementia—a practice she’d continue through twelve years and three cities—and started volunteering at a local nursing home, where she formed a deep friendship with an eighty-year-old woman over classic poetry and a shared neighborhood.

Opportunities are everywhere if you reach out

Bern-Klug’s academic career is a lesson in connecting with others and leaning into opportunity. She first enrolled at the UI—where she earned her undergraduate and master’s degrees—because an admissions counselor established a personal relationship with her family in Sioux City. Throughout and beyond her time at Iowa, Bern-Klug maintained a close friendship with her UI mentor and professor Hermine McLeran, the founder of the Aging Studies program. When Bern-Klug moved to D.C. to complete her MSW practicum, it was McLeran who introduced her to the work of the American Association of Dental Schools and suggested she apply to direct its Geriatric Education Project. (Of course, she got the job.) While in D.C., she often attended Senate Committee on Aging hearings on Capitol Hill. After hearing Georgetown professor Beth Soldo testify about the demography of aging in the U.S., Bern-Klug reached out to Soldo and promptly enrolled in Soldo’s applied demography MA program. There, she acquired a new skillset that led to positions at the National Institute on Aging (as social science analyst) and Pan-American Health Organization (as consultant).

Later, in 2020, close bonds with her Mexican relatives and a desire to explore aging in other cultures motivated her to apply for a Fulbright Faculty Scholar Award to the University of Guadalajara. She won that, too, connecting with other scholars interested in global aging, including many students.

“Connections make a big difference. I tell my students: make connections with fellow students and your teachers. Go to their office hours. You don’t have to have an agenda. If students tell us what they’re interested in, we may be able to connect them to resources within and beyond the university. Take that first step and reach out.”

Go out of your way to connect with your teachers, with people you admire, with people who know what you want to know, regardless of their age. You don’t have to be an extrovert; you just have to extend an email, then a hand. In most cases, you’ll receive more than you expect.

Nursing homes as community asset

We don’t typically think of connection as a benefit (or even a possibility) of life in a nursing home—if we think of nursing homes at all. “It seems like whenever you read about a nursing home in the paper,” Bern-Klug says, “it’s something bad—abuse or neglect.” But these incidents are rare—and according to her research, nursing homes actually serve as hubs of connection. Every day brings moments of meaningful connection between residents, family members, and staff; planned activities and rituals foster a sense of belonging; and many nursing homes cultivate connections with the surrounding community. “As we get older, we lose family and friends to disability, death, or moving,” notes Bern-Klug. “Our kids move out, we retire. It becomes harder to meet people we click with, but we still need that human network.” Whether they’re living independently or in long-term care facilities, people are much more likely to thrive when their social needs are met.

While long-term care centers exist on a spectrum of quality, as Bern-Klug, a member of the Iowa Nursing Home Quality Coalition, points out, all of them perform crucial functions and deserve community support. The contemporary nursing home addresses an exceptionally broad spectrum of needs: not only do levels of mobility and cognition vary widely among residents (as well as dietary needs and cultural traditions)—but so does age. Many nursing homes now double as bounce-back centers for those recovering from drug overdoses or severe accidents, which puts extra strain on the staff, many of whom barely make a living wage.

“Working in a nursing home—especially if you’re a direct-care worker, like a certified nurse aide—is hard, physically and emotionally, and the hours can be difficult. When we have people who do that work well and find it fulfilling, we as a society should be doing everything we can to support that person and that person’s family, because they’re a community asset.”

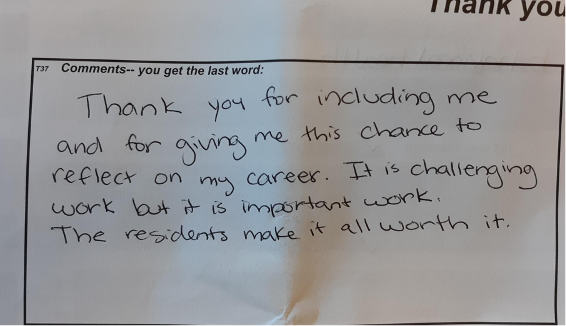

Every day, nursing home social workers are mediating roommate disagreements and counseling families struggling with the transition to long-term care. Nurse aides are brushing patients’ hair and delivering medications. Music therapists are strumming Beatles ballads and singing hymns. Activities directors are leading tie-dye workshops and book clubs. So far, Bern-Klug has conducted two national surveys of nursing home social service directors (see her 2024 co-edited collection, Nursing Home Social Work Research, for a discussion of recent findings); and one data point stands out: A large number of nursing home staff members love their job but can’t afford to stay in it—or they make personal sacrifices so that they can. For instance, says, Bern-Klug, “A lot of the nursing homes in Iowa City are excellent, but the staff don’t get paid enough to live in town, so they end up with a commute.” The solution is to support better compensation, healthcare benefits, and a well-defined career path for these workers, many of whom hold second jobs and are also caring for people at home. She’s particularly insistent that nursing home social workers receive funding for continuing education, given that federal regulations do not require them to hold a social work degree. (Please consider donating to the UI School of Social Work!)

Lend a hand

If nursing homes and their staff are community assets—and they most assuredly are—then “the community needs to show up,” says Bern-Klug. “Don’t wait till you need a nursing home to get involved.” There are easy, rewarding ways to support long-term care centers, even if you have only an hour in your schedule. You can:

help take care of the care center’s flower or vegetable garden;

sit, chat, read to, or play games with residents;

help residents set up video calls with their families;

help with social events and art/music activities;

help the staff decorate for special occasions or holidays; and

write to your elected representatives asking for staff supports.

You can also send thank-you cards to the staff, nominate a direct-care worker for special recognition, or show up at events that honor them. You can advocate for better wages and benefits, as well as realistic staffing ratios. And of course, if you have children at home, you can facilitate their interactions with older adults—and not just one or two, either. As Bern-Klug puts it, “If you filled a room with eighty-five-year-olds, you’d meet people who were running marathons and people who can’t roll over by themselves. People who’ve had twelve children and people who chose not to have kids. The longer we live, the more different we become. Most young people don’t realize that.”

You might help your local elementary school set up a program where older adults read to children or bring your kids to community events that are likely to attract participants from different generations. Intergenerational connections can occur organically when older people are employed as grade-school cafeteria workers, bus drivers, custodians, and classroom aides.

And whatever your age, invest in your own social connections!

Hear more from Mercedes Bern-Klug at October 1 Obermann event

To that end, please join the UI community on Wednesday, October 1, 2025, for a thought-provoking conversation between Bern-Klug and Amy Colbert, Professor of Management & Entrepreneurship and UI Distinguished Chair in the Tippie College of Business. Bern-Klug will share insights and data she’s gleaned from her accomplished career as a gerontological researcher as the two discuss the diverse ways we live, adapt, and flourish in our later years; the health and social benefits of nursing home care; the challenges facing residents, families, and staff at these centers; the vital role families and communities play in older adults’ lives; and the opportunities for connection and personal growth that continue throughout our later years. The event will take place at 4:30 p.m. in the Voxman Recital Hall and is free and open to all. Please contact the Obermann Center with questions and accessibility requests: obermann-center@uiowa.edu.

Recommended reading:

- International Perspectives on Older Adult Social Isolation and Loneliness — Open-access e-book, 2025. Kaye, L.W., Lubben, J., Bern-Klug, M., Ng, T.K., O’Sullivan, R.O., and Smith, M.L. (Eds.)

- Transforming palliative care in nursing homes: The social work role. Bern-Klug, Mercedes (Ed.) Columbia University Press, 2010.

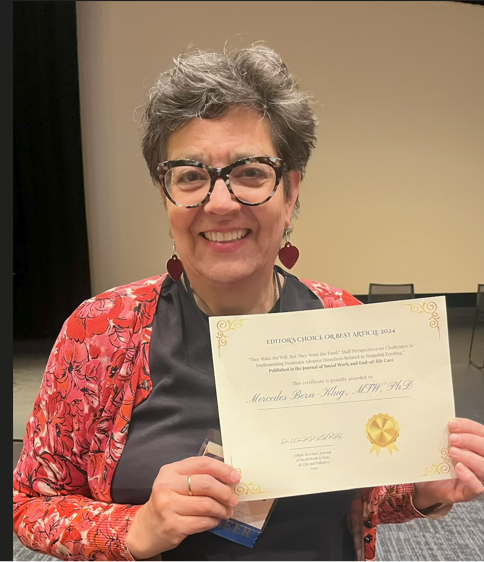

Below: Images from Mercedes Bern-Klug's scholarship and service. Click on a photo to see the caption.