Witnessing the Gravedigger

Promoting Breastfeeding in Women with MS

Dancing During War: Kowal Explores WWII Photo Archives

Searching for Red with Margaret Beck

Training Librarians to Preserve Community Memory

Using Virtual Reality to Train Math Teachers

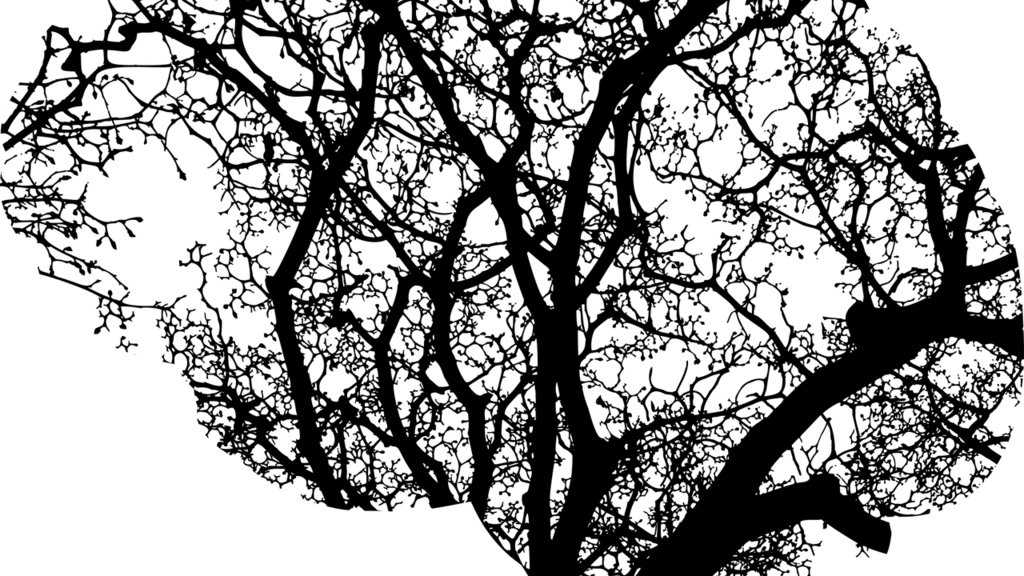

Brain Time: Rodica Curtu, Mathematical Biology, and the Perception of Time

Rural life, capitalism, and solidarity: Eric Hirsch on the challenges of climate change & entrepreneurship in highland Peru

Exploring the Echo Chamber: Brian Ekdale PI on $1M Grant to Study Social Media Algorithms & Extremism

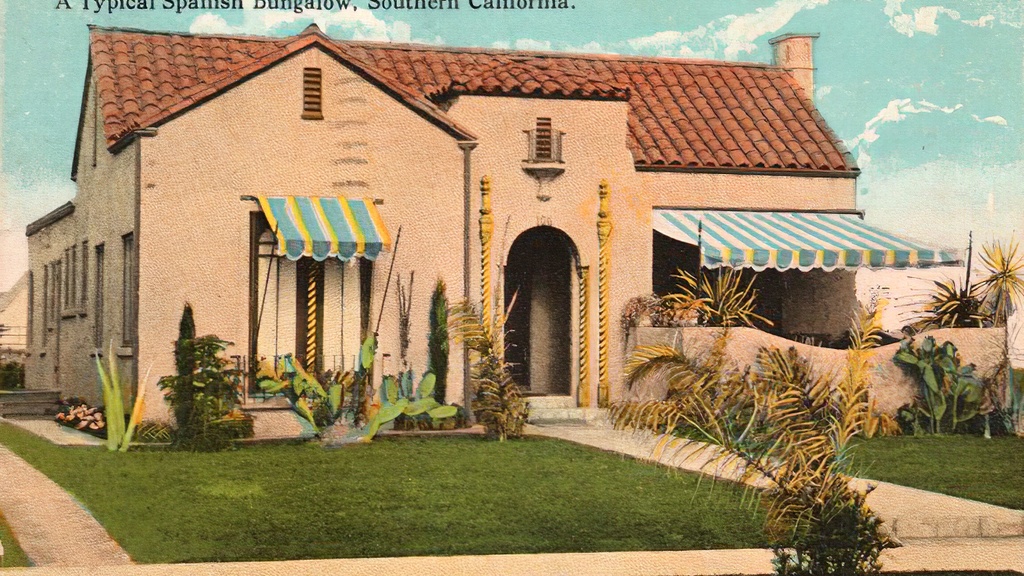

Uneasy Stories: Mary Lou Emery Explores the Paradoxical Cultural History of the Bungalow

Lost Language Found: Gordon Develops Tool to Improve Aphasia Diagnosis

An Aerial View—Remembering Esco Obermann

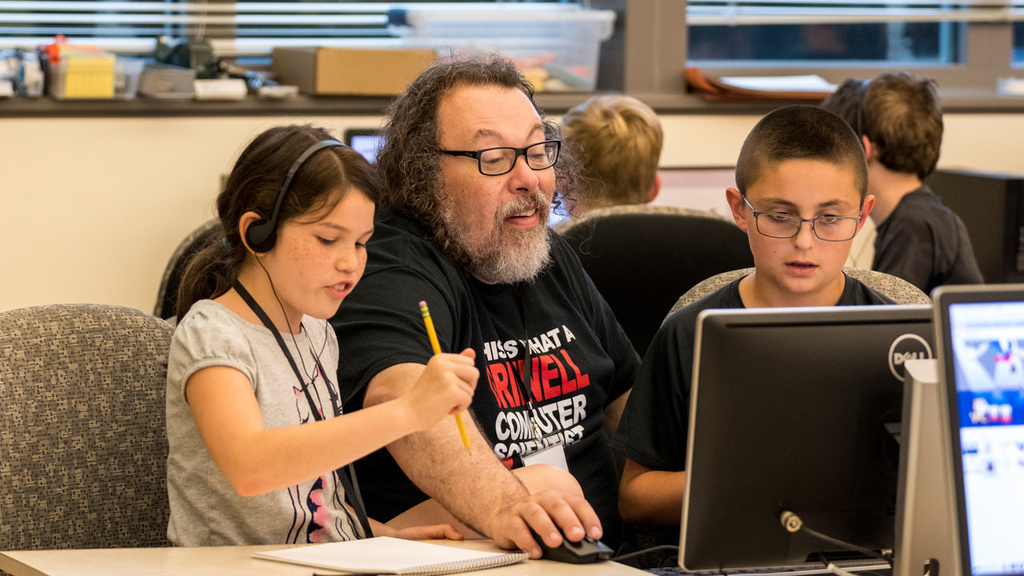

The Power of Programming: Sam Rebelsky

Making Space: Grad Institute alum blogs, podcasts for Black graduate students with mental health issues

The Archeology of Ten Minutes Ago: Preserving the Artifacts of Border Crossing

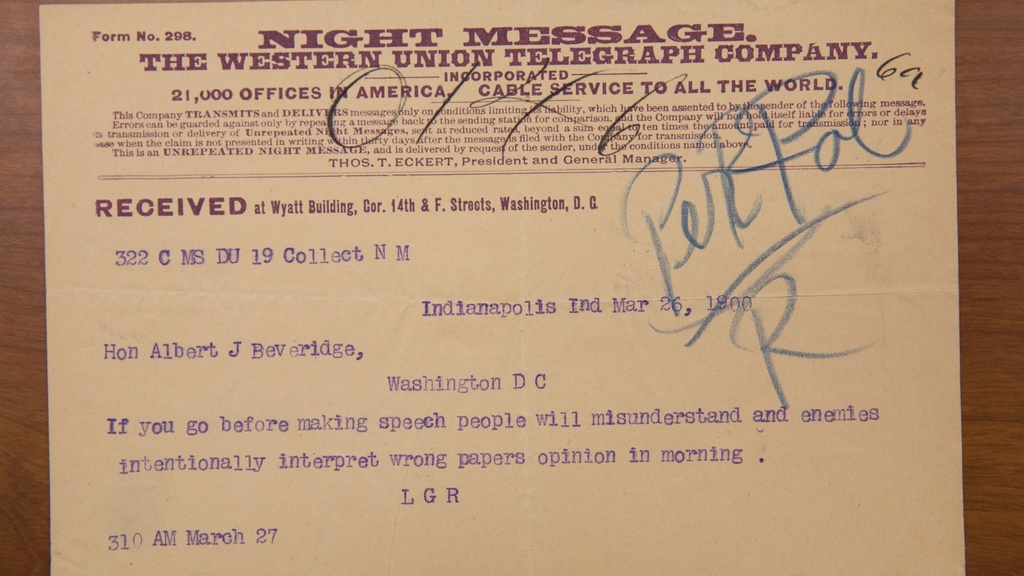

Typewriters for Eskimos: Imperialist Rhetoric & Puerto Rico

The Meek and the Mighty: Interdisciplinary Research Grant Explores Diversity Programs

Open-Access Tools Make Research Available to All

Rug-cutting robots

You’ve probably seen people dancing “the robot,” all stiff limbs and sudden stops—but how about robots dancing like people?

Meet Amanda. She’s a two-foot-tall humanoid robot with flexible shoulder, neck, hip, knee, and ankle joints that allow her to approximate human movements. She’s one of four interactive robots University of Iowa students are teaching to dance in a new course offered through the Departments of Computer Science and Dance in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

The class, aptly titled “Dancing Robots,” charges its eight students—seven undergraduate dance, computer science, and electrical engineering majors, and one performing arts graduate student—with choreographing a dance for the robots, then programming them to perform it.

The NAO H25 robots—Amanda, Christopher, Denise, and Alberto—were developed by Aldebaran Robotics for use in research and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education. ("NAO" is the company's futuristic spelling of "now," and H25 refers to the humanoid robots having 25 degrees of freedom.) Their behavior can be controlled by computer, via the programming languages Python, C++, and Java, or via the graphical programming tool Choregraphe, whose user-friendly interface facilitates the process for those with little programming experience.

Still, it’s not easy to tell a robot what to do. “Since the robots are relatively recent models,” says Sean Laughead, a senior dance major from West Des Moines, “there isn't much technical support online, and we're really having to pioneer different strategies to articulate movement. Whenever we achieve one of our goals, it's really exciting—even if that goal is just to have the robot wave its hand.”

Humanities gone spatial

If you’ve used Google Maps recently—with options to view a city’s weather, terrain, traffic conditions, bike trails, even videos, photos, and relevant Wikipedia articles—you know a map can tell you a whole lot more than where you are and where you’re going.

Geographers know this better than anyone. For more than a century, they’ve built and used maps to study the physical, climatic, economic, political, and cultural characteristics of different regions, and the relationships between them. Maps are especially essential for identifying patterns: even if you know the rates of, say, soil erosion across 10 Iowa counties over the past five years, the data may not resonate until you see it represented on a map. Plot multiple sets of data alongside each other, and suddenly patterns emerge and questions arise: Could erosion be linked to urban sprawl?

Now, a new, some might say unlikely, group of scholars are using digital mapping technology to answer their own questions:

- "Would Robert E. Lee have been able to see Union forces on the far side of the battlefield when he ordered the notorious Pickett’s Charge?"

- "Why did African American families settle almost exclusively on the near north side of St. Louis in the 1940s?"

- "How and where did globetrotting, 17th-century Dutch traders leave marks of their flourishing culture?"

Humanities researchers—historians, linguists, philosophers, cultural studies researchers, and literary scholars—are increasingly taking a spatial look at what they do, and the interactive, richly sourced maps they’re creating are opening up new opportunities for humanities scholarship, teaching, and outreach.

Essential English

Jin-A Park can order a complicated coffee with perfect English grammar, ask an American classmate to lunch with ease, and keep up with her linguistics professors’ mile-a-minute lectures on morphoxyntax and phonological theory—but, that certainly wasn’t always the case for the South Korean native.

When she first came to the U.S. to attend high school, she had limited English and avoided any social situation that required speaking.

“I didn’t know any English, any American culture,” she says (though, to be fair, she did have some English, having studied the language since grade school). “All my high school classes were in English, but I still needed classes on how to speak English.”

When she entered the University of Iowa in 2011, she expected to be thrown directly into a degree program, where, as in high school, she’d have to sink or swim. But instead, she encountered a network of teachers and administrators committed to supporting students who speak English as a second language.

Maureen Burke directs the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences’ English as a Second Language (ESL) Programs, which provide ESL support for the UI’s approximately 3,000 international students for whom English is a foreign language.

Though most international students learn English through their home countries’ school systems, much of this education, says Burke, is geared toward passing one of the high-stakes language exams required for admission to U.S. universities, such as the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) or International English Language Testing Services (IELTS).

“Sometimes students who do well on those tests find it difficult to use the language in any other environment. They’re taught ‘use this phrase in this kind of situation,’ and they memorize that,” Burke says.

As a result, she says, many students arrive unprepared for work in dynamic U.S. college classrooms.

Welcome to Iowa, 'Escritores'!

For a year, the only thing Paula Lamamie de Clairac Garrido knew about the University of Iowa was its mailing address.

She’d been working as a bookstore clerk in her native Madrid, Spain, when she met Ana Merino, associate professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at the UI, who’d stopped by to collect source texts for her Spanish creative writing classes at the university.

“For months, she had me shipping all these books to the University of Iowa,” Lamamie laughs, “and I didn’t even know what it was. I had no idea it was this famous place for writing.”

Eventually Merino discovered that Paula had a degree in philosophy, wrote poetry and book reviews, danced, and was working on a novel—“so she asked me,” says Lamamie, “‘What are you doing next year?’ Then she told me about the writing program she was developing, and I went online right away to see where Iowa was.”

Lamamie is now a second-year student in the UI’s Master of Fine Arts in Spanish Creative Writing program. Housed in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the two-year program allows Spanish-speaking students to develop their writing talents in their native language while working with established writers from across the Spanish-speaking world.

Core faculty are Merino, the program director and a poet and comics scholar from Spain; Salvadoran writer Horacio Castellanos; and Chilean crime novelist (and, as it happens, newly appointed ambassador to Mexico) Roberto Ampuero. Spanish poet Luis Muñoz and Mexican-American novelist Luis Humberto Crosthwaite are this year’s visiting faculty.

Writing new roles, righting old wrongs

Interior scene: a college theater classroom

Professor: Who are the first five playwrights that come to mind? Anyone?

Student: Shakespeare, Chekov, Miller, O’Neill, Beckett.

Professor: OK, and who would you say are their best characters?

Student: Iago, Uncle Vanya, Willy Loman, Hickey, Estragon…

Professor: Good—complex roles, lots of stage time. Any female characters we could add to the list?

Student: (drumming fingers on desk): Um...Lady MacBeth?

Most of us, asked to list major female playwrights and stage roles, could probably count the number we know on 10 fingers, while we’d need five or six hands to list their male equivalents.

The reason is simple, says Alan MacVey, director of the UI Division of Performing Arts and chair of the Department of Theatre Arts: “There are many more male than female playwrights in the industry, and more good stage roles for men than for women. It’s a well-known problem.”

“It’s particularly difficult to find good scripts for performing arts education,” he adds, noting that many substantial female roles—central, complex character roles rather than supporting or stereotypical roles—are for characters middle-aged and older, which can be a struggle for young actors to portray.

That’s why, in 2010, MacVey proposed that the Big Ten Theatre Consortium (the group of theater department heads at Big Ten Conference universities) establish a commission program to support female playwrights and provide female theater students and professional actors with strong roles. The program would not only be the first of its kind, but would also represent the first time the Big Ten Consortium schools collaborated on a project. MacVey’s colleagues embraced the idea and set about crafting the details.

Fluency and Fun: UI SPEAKS Helps Kids Who Stutter

In a sunny, second-story room at the Wendell Johnson Speech & Hearing Clinic, six kids perch on brightly colored chairs arranged in a circle. Beside each child sits his or her personal speech coach for the week, so designated by her badge. There is some fidgeting, some excited chatter, before one of the coaches asks, “So who wants to lead the group today?” A boy in a blue shirt shoots up a hand, and the clinician hands him an index card. “Question number one!” he reads aloud, tripping a little over the n, “What have you learned from camp so far?”

It has only been one day, but the children—many of whom take pains to avoid being called on at school—are eager to answer. As the boy in blue calls their names, they respond: “That it’s OK to stutter.” “Just because you stutter doesn’t mean you’re not normal.” “If you practice, you’ll become more fluent.” “To be determined!” “If people make fun of you, you can ignore them because they don’t understand, but you understand.” Of course the answers don’t come quite as effortlessly as this: there are hesitations, pauses, repetitions of words and syllables, to which the speech coaches respond with small words of encouragement, like “easy” or “focus.” And yet the others do not become impatient or interrupt, or worse, laugh. They know what it’s like to stutter; they wait. They listen.

The kids are participants in the UI SPEAKS week-long stuttering camp hosted each summer by the Department of Communication Sciences & Disorders in the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences. Because there is no known cure for stuttering—a condition experienced by some 3 million Americans—the goal of the program is to offer a safe and supportive place where children aged eight to twelve can learn strategies to increase their speech fluency, practice their speech, meet other children who stutter, and learn to talk openly about the problem. “We help to demystify it,” explains Toni Cilek, director of the camp and a clinical associate professor in the Department. Cilek established the program in 2006 with the recognition that early intervention is important in the successful management of stuttering, emotionally as well as linguistically. “We want the kids to learn to accept their stuttering, but we also want them to try to improve it,” she says, noting that for many people—especially children—stuttering, untreated, can be a source of anxiety, fear, anger, and shame. The summer, she says, is a good time for the kids to do intensive practice and to focus without the distractions of school.

Decibels and Democracy

The louder the voice, the cloudier the choice: So says research led by the University of Iowa, which found that a single loud voice can skew the result of voice votes, a common decision-making feature in American public life.

Voice voting is used at civic, local, and county governmental meetings. It's also employed regularly in Congress (especially the Senate) and in state legislatures to pass resolutions. The format is simple: A presiding officer states a question, and the group that replies either yea or nay the loudest is declared the winner.

But the technique can turn out to be confusing and even produce erroneous results, researchers at the UI and at the National Center for Voice and Speech argue in a paper published this month in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America.

“All voters should realize that a soft (voiced) vote is basically an abstaining vote and that one loud vote is equivalent to many votes with normal loudness,” says Ingo Titze (pronounced TEET-Zah), professor in the UI’s Department of Communications Sciences and Disorders in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and corresponding author on the paper. The researchers calculate it would take at least 40 normal loudness voices to overcome the bias of a single loud vote, in order to establish roughly a two-thirds majority.

Sioux City social work pioneer

Say you’re from Puerto Rico, and your family’s just moved to Iowa for a handful of jobs in the energy industry. You’re settling in okay, except that your son-in-law has been having visions, more of them than usual, and can’t focus at work. A friend suggests the local mental health clinic, and though no one in your family’s ever been to such a place, you’re desperate; you stop by to make an appointment.

But family members, it turns out, cannot make the appointments—they’re not even allowed to join in the sessions. There are no Spanish-speaking counselors, either, and when you try to explain about the visions—the angels your son-in-law sees in the hallways, la Virgen, his late father—you’re met with skeptical eyebrows and words like psychosis. You begin to think maybe he’s better off on his own when you glimpse the little sign on the receptionist’s desk: INSURANCE OR CREDIT CARD ONLY. That settles that; your family has neither.

It’s scenarios like this that University of Iowa alumna Meg Bessman-Quintero, a Licensed Independent Social Worker (LISW)—the only bilingual, master's-level mental health therapist practicing in the Sioux City area—works hard to avoid.

At Catholic Charities in Sioux City, Iowa, where she counsels primarily Spanish-speaking immigrants and their families, clients can use cash to pay the sliding-scale fee—as little as seven dollars per session; bring their families into the counseling room with them; and, most importantly, discuss their concerns, symptoms, and treatment plans in their native language (which, research shows, makes the therapy twice as effective).

Every new client is welcomed in Spanish: “Good morning, I’m Meg, the therapist. Are you ready to start? Will your family be waiting here for you or were you hoping they could join us? Is it all right if we use tú” (a more familiar form of Spanish)?"